The problem of evil is a philosophical and theological conundrum questioning how the presence of evil is compatible with the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good deity. If Allāh (God) is not aware of the presence of all evil, then he is not omniscient. If he lacks the power to prevent all evil, then he is not omnipotent. If he is omniscient and omnipotent but allows for evil to exist, then some may argue that he is not good. Skeptics may argue that since evil exists, then Allāh does not exist or that it is unlikely that he exists. This problem has prompted many theists and philosophers to develop diverse theodicies, which are essentially explanations that seek to reconcile the presence of evil with the existence of Allāh.

What grounds objective morality?

The first problem with the problem of evil is to define evil. What is evil? To put it broadly, evil is that which is done without justification. The good individual is the just individual, and the evil individual is the unjust individual. The issue is that human subjectivity will lead many people to disagree on what makes an action justifiable [1]. These disagreements may lead one to question whether morality is objective or subjective.

When something is objective, it means that it is fact-based and not influenced by personal feelings or opinions. For example, 2 + 2 = 4 is an objectively true mathematical fact, and it is not true merely because everyone has agreed that it is true; it is true regardless of agreement or disagreement. When something is subjective, it means it is influenced by personal feelings or opinions. For example, one may find the taste of chocolate ice cream to be more pleasant than the taste of vanilla ice cream. Is the taste of chocolate ice cream objectively better than the taste of vanilla ice cream? The answer is no; one can only consider the taste of a particular food or drink to be better than another on a subjective basis, as taste is ultimately a matter of individual preference [2].

As for morality, some people consider it to be objective, but why do they consider it to be objective? Many would argue that certain actions spark a strong moral intuition within them to such an extent that they feel that there must be an objective moral reality. For instance, they may find the idea of torturing others for amusement deeply disturbing, and due to their disgust, they may want to claim that torturing people for amusement is not merely evil subjectively but is objectively evil. If it is objectively immoral to torture others for entertainment, then a person would be wrong for claiming otherwise, but if morality is subjective, then a person is neither wrong nor right for believing or for not believing that it is evil to torture people for entertainment. In this case, whether one believes it is evil or not is no different than whether a person prefers chocolate ice cream or vanilla ice cream. Since intuition varies between individuals, another person may not find it repulsive to torture for entertainment. Therefore, to claim that an action is objectively moral or immoral because one strongly feels it to be so does not prove objective morality. To use intuitive feelings to argue for an objective moral reality, even if they are strong feelings, is no different than someone arguing that chocolate ice cream tastes better than vanilla ice cream.

Additionally, those who claim that morality is objective may be asked the following question: what principles constitute the foundation of objective morality? Most people would state principles such as beneficence, fairness, honesty, minimizing harm, and so on. However, another person could say that the principles of objective morality are to maximize harm, minimize well-being, unfairness, dishonesty, and so on. Why should one set of principles be chosen over another? If one answers that most people would want to live in a world where the first set of principles is taken as the basis for objective morality, then this becomes a matter of preference, which collapses into subjectivity. Furthermore, even if everyone agreed on the same principles, they would disagree on the application of those principles. Take for example the principle of fairness; what one person considers to be fair may not be fair according to another individual.

Moreover, these principles may conflict with each other in certain cases. Imagine that one had certain knowledge that a particular child was going to mature and kill a large number of innocents and that the only way to prevent these murders is to kill the person as a child. Is it objectively moral or immoral to kill this person as a child? Many people may answer that it is objectively good to kill this child with the intention of saving the innocents because it leads to increased well-being and reduced harm overall, while others may answer that it is objectively evil to kill this child because they may hold that it is wrong to kill or punish someone for a crime that they have not yet committed. In this controversial example, some may hold maximizing well-being and minimizing harm as an objective principle of morality, while others may hold that it is wrong to kill or punish someone for a crime that they have not yet committed as an objective principle of morality, so which is it? Perhaps both may be taken as objective moral principles, but in this scenario, these principles conflict with each other, so which one should be prioritized?

How can those who claim that morality is objective know what grounds objective morality when people differ on its foundational basis and application? Perhaps they may appeal to the majority and say that the majority view is what grounds objective morality. This is problematic because the majority view could change, and this undermines what it means to objective. Furthermore, imagine that the Nazis had taken over and imposed their world order after World War II and that the majority of people aligned with Nazi ideology, and anyone who challenged this ideology was crushed. Would Nazi ideology now be objectively moral, and to oppose this ideology would now be objectively immoral? Most people who believe in objective morality would reject this.

There is no objective morality without Allāh. What is the Euthyphro Dilemma?

Theists recognize that Allāh is a necessary foundation for objective morality because he transcends human subjectivity. However, to use Allāh as the foundation for objective morality has been met with questions and concerns. A famous dilemma known as the Euthyphro Dilemma goes as follows: do the gods love something because it is pious or is it pious because it is loved by the gods? This dilemma can be reworded to conform to a monotheistic worldview as well. Does Allāh command something because it is good or is it good because Allāh commanded it?

Some sects, such as the Muʿtazilah, believed that Allāh commands something because it is good and that he prohibits something because it is evil. This makes morality objective and independent of anyone, including Allāh, and actions would have intrinsic moral value, meaning actions are moral or immoral in of themselves. In fact, this is why the Muʿtazilah believed that moral truths can be discerned without waḥy (revelation). If so, why then would the Qurʾān give moral directives? One could say that people may be able to discern general objective moral truths and principles without revelation, but revelation is still required to provide guidance on specific moral issues. However, people disagree on what are general objective moral truths and principles, so this goes back to the previous question: how can those who claim that morality is objective know what grounds objective morality when people differ on its foundational basis and application?

Another problem with the view of the Muʿtazilah is that Allāh can only be good and just by adhering to an external moral standard. This appears to compromise Allāh’s omnipotence and sovereignty. Furthermore, how would one know that Allāh commands what is good and prohibits what is evil? If morality is independent of Allāh, then one must first know objective morality in order to know that Allāh commands what is good and forbids what is evil. If one claims to know that Allāh commands what is good based on the fiṭrah, then this too has problems. The fiṭrah is the innate predisposition that inclines people towards the worship of one deity. The innate moral intuitions that people have are also a part of the fiṭrah. Virtually everyone finds it good to give ṣadaqah (charity) to the poor and needy, so one could say that this a part of the fiṭrah and that Allāh has encouraged people to give ṣadaqah in the Qurʾān. Since the Qurʾān lines up with the moral intuitions of people, then one may claim that Allāh commands what is objectively good because his commands are in line with the fiṭrah. This view is problematic because Allāh created the fiṭrah. If he willed, he could change the general moral intuitions that people have. It is not impossible for Allāh to create people who are disgusted with the act of giving ṣadaqah, such that when they see someone giving ṣadaqah, they remark, “How evil! That person is giving ṣadaqah.” Thus, it does not appear correct to use the fiṭrah to argue for objective morality.

As for Sunnīs, they hold that something is good because Allāh commands it, and something is evil because Allāh prohibits it. This view is known as Divine Command Theory or theological voluntarism, and this is the opposite view of the Muʿtazilah. This view is problematic for those who believe that morality is objective because if Allāh willed, he could command tomorrow what he forbade yesterday, and this would render morality subjective and arbitrary. In response, some Sunnīs, particularly the Ḥanābilah and the Māturīdīyyah, would reply that Allāh’s commands stem from his character, which is eternal and good, and this is a modified type of Divine Command Theory. If his character is good, then his commands would be good, and if his character is eternal, then his commands which stem from his character would not be arbitrary, as Allāh would not arbitrarily change his commands for no reason.

While this seems like a reasonable response, on closer inspection, there are still problems with this view. If one claims that Allāh’s character is objectively good, one must first know what is objective goodness before labeling anything as objectively good. If one chooses to label Allāh as objectively good because he meets a particular criteria or standard of goodness, then morality would be objective but external and independent of Allāh, and this would collapse into the view of the Muʿtazilah. If one says that Allāh is himself the objective standard and source of goodness, the question is why is Allāh the objective standard and source of goodness? If one arbitrarily selects Allāh to be the objective standard and source of morality, then this would render morality subjective and contradict objective morality. If one says that Allāh is objectively good because he is perfect, then what is meant by perfect? If one means that Allāh has no deficiency in his attributes, then this is true in an objective sense, as Allāh is omniscient, so he has no deficiency in his knowledge, and he is omnipotent, so he has no deficiency in his power, and so on. However, a perfect entity can also refer to something that has all desirable characteristics, but this would render perfection subjective as what is desirable to one person is not necessarily desirable to another. Of course, most people would consider omniscience and omnipotence to be desirable and perfect, but as strange as it would seem, one could prefer ignorance and weakness.

Nevertheless, say that a person uses the first definition of what it means to be perfect and says that Allāh is objectively good because he possesses maximal ṣifāt (attributes), such as omniscience, omnipotence, and so on. A question resembling the Euthyphro Dilemma can be posed: is Allāh good because of his ṣifāt or are his ṣifāt good because he possesses them? If one chooses the latter, then goodness becomes arbitrary; as long as something is attributed to Allāh, then it is good. As per this view, even if he had deficiencies in his ṣifāt, then these ṣifāt would be good, but this contradicts the first definition of perfection. If one answers that Allāh is good because of his ṣifāt, this may raise a problem, as one could say that Allāh is not identical to his ṣifāt, which would entail that he is not identical to goodness, but this would not be a problem for those affirm divine simplicity, which is a doctrine that holds that Allāh is identical to his ṣifāt. Sunnīs reject divine simplicity and believe that Allāh is not identical to his ṣifāt, but they would reply that this is not a problem because they believe that the ṣifāt are inseparable from Allāh, and so goodness is inseparable from Allāh.

Another reason why Muslims take Allāh as the objective standard and source of morality is because he is the Creator and Owner of everything. All of creation is his property. He owns everything, and so he has the right to do anything. As per this view, it is not that Allāh chooses to be objectively good and just, but it is logically impossible for him to be objectively evil and unjust. Even if he were to punish an innocent for eternity, this would not be evil because this would be within Allāh’s rights. While all Sunnīs would agree with this, the Ḥanābilah and the Māturīdīyyah would say that since Allāh’s character is eternal, then he would not do something like this because it is not in his character to do such.

Indeed, a modified Divine Command Theory is perhaps the best way for theists to hold to objective morality without making it separate from Allāh. As per this view, it is not that Allāh adheres to an external moral standard, making morality objective but independent from him, nor does he invent the moral standard, making morality subjective, but he is himself the objective moral standard. There appears to be no way to ascertain objective morality without Allāh, as all other moral theories seem to collapse into some sort of subjectivity or arbitrariness.

The view that morality is subjective

The Ashāʿirah, a group within Sunnī Islām, believes that morality is subjective because, according to them, it is possible for Allāh to issue commands that do not necessarily reflect his character. Recall that all Sunnīs believe that something is good because Allāh commands it, and something is evil because Allāh prohibits it. However, the Ḥanābilah and the Māturīdīyyah say that since Allāh’s commands stem from his eternal and unchanging character, he would not arbitrarily change his commands for no reason, but the issue is not if Allāh would do such, but it is a matter of if Allāh could do such. If someone rejects that Allāh is able to do such, then this would undermine Allāh's omnipotence. However, someone could reply that it is a logical contradiction for Allāh to issue a command that does not reflect his character, and as explained in a previous article, it is impossible for Allāh to create a logical contradiction, but this does not undermine his omnipotence whatsoever. Nevertheless, if the Ashāʿirah are correct, then morality would be subjective because it could change.

The Qurʾān explicitly presents Allāh as commanding people to be faithful to their spouses, and without doubt, Allāh’s character is such that he detests infidelity, but does Allāh have the power to command people to cheat on their spouses just by arbitrarily willing it? If yes, then morality is subjective because it is invented. If no, then either Allāh is not omnipotent, but this is false because he is omnipotent, or it is a logical contradiction for Allāh to issue this command, and this is why it would be impossible for Allāh to order people to infidelity. However, the view of the Ashāʿirah seems to be strong because while the character of Allāh is eternal and unchanging, Allāh does create what he hates, such as actions of kufr (disbelief). If Allāh can create what he hates, what would make it impossible for him to command what he hates?

It is to be noted that Muslims believe that legislation has changed. Allāh has sent various prophets and messengers to people throughout history, and they taught the same ʿaqīdah (creed). However, the Sharīʿah (Islāmic Law) would change based on people’s circumstances in their respective eras. Muslims believe that Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ was given the final Sharīʿah, but even the rulings of his Sharīʿah can change depending given certain conditions. For instance, pork is ḥarām (forbidden), but if a Muslim is starving to death, he must eat pork in order to survive if no other sustenance is available. The Ḥanābilah and the Māturīdīyyah would say that this change in ruling is not arbitrary; it is based on Allāh’s character, and his character is such that while he has forbidden pork, he would rather a person eat it to survive if no other food is available. Non-arbitrary changes to the Sharīʿah do not prove that morality is subjective, but if Allāh can make arbitrary changes to the Sharīʿah, then morality would be subjective.

The case for Islām under both objective and subjective moral frameworks

There is no compelling moral theory that can ground objective morality without Allāh. In fact, a moral argument can be made to argue for the existence of Allāh.

- Morality is objective.

- There cannot be objective morality without Allāh.

- Therefore, Allāh exists.

This syllogism is valid. The first premise is incredibly controversial, but if a person does accept that morality is objective, then the following question arises: what grounds objective morality? As mentioned earlier, there seems to be no way to ascertain objective morality without Allāh, as all other moral theories that exclude Allāh seem to collapse into some sort of subjectivity or arbitrariness. Thus, it appears that the second premise holds and that there cannot be objective morality without Allāh. Therefore, if one believes morality is objective, and objective morality cannot be true without Allāh, then one must accept the existence of Allāh. The only way to escape this conclusion is by denying that morality is objective, or it must be demonstrated that there can be objective morality without Allāh. However, it is to be noted that many religions claim that Allāh grounds objective morality, yet they disagree on moral directives. A religion cannot claim to have objectively moral directives until it proves that its sets of moral directives actually came from Allāh. Muslims claim that Islām is true because it presents a sound concept of Allāh, the Qurʾān is preserved and is inerrant, and Islām presents a multitude of miracles that demonstrate that it is a divinely sanctioned religion. Once one accepts this, then one can accept that the Qurʾān gives objectively moral directives because these directives came from Allāh, and people cannot be objectively moral unless they embrace Islām.

Moreover, even if morality is subjective, people should still obey Islām’s moral values instead of their own. The reason for this is that Islām can be shown to be true based on objective proofs and evidences, such as miracles and prophecies. If Islām is true, then Jannah and Jahannam are true. Jannah is a garden and an abode of eternal peace and happiness that has been prepared for believers, while Jahannam is hell and a prison designed to torture disbelievers forever. If one prefers to maximize well-being and to minimize harm, then the best way to do this is to embrace Islām and to be steadfast upon the religion until one dies and meets Allāh in such a state so that one attains salvation. Even if it is not objectively good to maximize well-being and to minimize harm, most people find it to be subjectively good, so people can still be persuaded into joining the religion for this reason.

Rewording the problem of evil as the problem of suffering

Returning to the problem of evil, one may accuse Allāh of being objectively evil for not preventing or neutralizing evil despite being aware of its existence. If one accuses Allāh of being objectively evil, then one must first prove that morality is objective. Then, one must prove what principles constitute the foundation of objective morality, but people differ over these principles and their application. Muslims can simply reply that objective morality is grounded in Allāh, and so he would be exonerated from any accusation of being objectively evil. If morality is subjective, then one cannot say that Allāh is objectively evil. Due to the differences on what exactly it means to be evil, the problem of evil should be reworded as the problem of suffering, as everyone agrees that suffering is an objective aspect of reality. The problem of suffering can be made in the form of a syllogism.

- An all-merciful being who is omniscient and omnipotent would prevent or neutralize suffering.

- Suffering exists.

- Therefore, an all-merciful being does not exist or it is not omniscient or omnipotent.

Why the problem of suffering is not problematic for Muslims? All-Loving and All-Merciful or Most Loving and Most Merciful?

The syllogism that has been presented is valid, but it is not problematic for Muslims because while Islām does teach that Allāh has no limit to his mercy, it does not teach that Allāh is all-merciful in the sense that he shows everyone absolute mercy every moment; the same can be said regarding his love. According to Islām, three of Allāh's names are Ar-Raḥmān (the Most Merciful), Ar-Raḥīm (the Especially Merciful), and Al-Wadūd (the Most Loving) [3]. Allāh is Ar-Raḥmān because he shows mercy to everyone in this worldly life (dunyā), including kuffār (disbelievers). Allāh's mercy pervades and encompasses all of reality; any ease or comfort in this world, from the tiniest cell being nourished to the order of the cosmos that allows life to flourish, is due to his mercy. If by an all-merciful being, one means that this being shows mercy to everyone, then Allāh is all-merciful, but it cannot be said that Allāh is all-merciful in the sense that he shows everyone complete mercy every moment because then there would be no suffering whatsoever.

As for the name Ar-Raḥīm, this refers to the specific mercy that Allāh shows to specific people. For example, the believers will be granted Allāh’s mercy in Jannah perpetually, while the kuffār will be far removed from his mercy in Jahannam forever. The specific mercy of Allāh is reserved for whom he loves, such as the believing allies of Allāh.

Had Islām taught that Allāh was all-merciful or all-loving, then the problem of suffering would have been an actual problem for Muslims. Any religion that teaches that Allāh is all-merciful or all-loving falls into contradiction because the existence of suffering is simply irreconcilable with the existence of an all-merciful or all-loving being that is also omniscient and omnipotent.

Even if Allāh is not all-merciful or all-loving, why allow any suffering?

One could ask that even if Allāh is not all-merciful or all-loving but is only the Most Merciful and the Most Loving, why allow any suffering? Many theologians and philosophers have tried answering this question. Some have said that certain character traits can arise out of suffering as opposed to a world where suffering is not present; this is known as a soul-making theodicy, which proposes that suffering is critical for spiritual growth. For example, say that there is a building engulfed in flames, and a firefighter exhibits great courage by charging in the building in order to save people. Courage would not exist in a world where there is no suffering. This type of theodicy attempts to show that there is a greater ḥikmah (wisdom) underlying suffering. Sometimes the ḥikmah is apparent, and sometimes it is not as clear, but even if it is not clear, that does not mean there is no ḥikmah. Consider a child that is prevented from eating candy constantly by his parents. The child may think that his parents are cruel because he cannot comprehend the ḥikmah of the parents, while the parents realize that it is not beneficial for the child to eat candy excessively.

This is a semi-reasonable theodicy, but it is insufficient because the suffering in the world often leads many to behaviors that are generally considered by most to be adverse. Furthermore, Allāh is omnipotent, and so he can make people stronger and wiser without them having to undergo any adversity. The same applies to contrast theodicy, which posits that it is necessary for there to be evil so that one can understand and appreciate goodness or that it is necessary for there to be suffering so that one can understand and appreciate well-being. This theodicy falls into a similar problem that the soul-making theodicy falls into: Allāh is omnipotent, and so he can make a person appreciate and understand goodness or well-being even without the presence of evil or suffering.

The most common and arguably the strongest theodicy is the free will theodicy. This theodicy argues that human free will is responsible for much suffering. Proponents of this theodicy argue that Allāh can make a world without suffering, but this would compromise human free will because a lot of suffering originates due to human free will. The same objection made to the previous two theodicies can be made to this theodicy: Allāh is omnipotent, and so he can make a world without suffering without compromising human free will. To deny this would be to deny Allāh’s omnipotence. The only way one could reasonably defend this theodicy without negating Allāh’s omnipotence is to demonstrate that it is contradictory, and therefore impossible, to create a world free from suffering without compromising human free will. Many of the proponents of this theodicy believe in Jannah, which is a garden of everlasting peace and happiness in the ākhirah (hereafter). Jannah is generally considered to be an abode whose inhabitants have free will, yet there is no suffering in Jannah. Of course, one may hold the view that the people of Jannah do not have free will, but almost no one holds this view.

Moreover, Allāh could preserve the free will of people while removing their inclinations that tempt them towards behavior that bring about suffering. Proponents of free will theodicy may counter by stating that this would not be free will, but this leads to the question of what exactly is meant by free will. If by free will, one means that a person has the ability to act voluntarily, then people would still have free will because even if they no longer incline towards performing actions that bring about suffering, they can at the very least voluntarily perform actions that bring about well-being. Why would Allāh not create a world wherein people only perform those actions that bring about well-being instead of suffering? Some may answer that perhaps Allāh allows people to perform actions that lead to suffering because he tests people, and the Qurʾān confirms that this dunyā was created as a test for humanity and the Jinn in order to fulfill their purpose, which is to worship Allāh. Those who die while fulfilling this purpose will go to Jannah, and those who fail will enter Jahannam. To know that the dunyā is a test cannot be known without revelation, but once one accepts the Qurʾān as true revelation, then one discovers that the reason for suffering in this world is that Allāh is testing his creation.

Why does Allāh not reveal himself?

The fact that Allāh has made reality a test answers why he does not reveal himself. Despite this, he has not made this test one of blind faith; there are numerous proofs and evidences for the truth of Islām. One does not need to see Allāh in order to know that he exists or that Islām is true. It is a fallacy to assume that one can only know something by witnessing it. It is known that gravity exists, even though it has not yet been observed, because its existence is known through its effects. Moreover, even if Allāh did reveal himself, what guarantee would a person have for believing in him? Shayṭān (Satan) knows that Allāh exists and that Islām is true, yet he falls into kufr (disbelief) by blaspheming [4].

Why make reality a test?

That Allāh has created the dunyā as a test explains why there is suffering. However, if one digs deeper, one can ask why create any test in the first place? In fact, why not simply put everyone in Jannah without any test? This would by far be more merciful than creating a test. Nevertheless, Allāh is not obligated to test anyone, nor is he obligated to do anything. If he so willed, he did not have to create anything.

However, it is due to Allāh’s character that he decided to test some of his creation. Many people are fixated with Allāh’s mercy and love but often neglect his other names. Allāh is Al-Ḥākim (the Judge), so what is there to judge if there is no suffering, conflicts, trials, or tribulations? Allāh is Al-Ghafūr (the Most Forgiving), so what is there to forgive if there is no sin? Allāh is Ar-Rāfiʿ (the One who Exalts) and Al-Muʿizz (the Honorer), and he is Al-Khāfiḍ (the One who Abases) and Al-Mudhill (the Giver of Dishonor). He exalts and honors the believers by entering them into Jannah, and he abases and dishonors the kuffār by casting them into Jahannam. Thus, Allāh chose to test some of his creation because it is within his character to do so, but one cannot go further than this because Allāh’s character is beginningless. To ask why is Allāh’s character the way that it is gives way to futility because one cannot ask ‘why’ regarding something that is beginningless.

Does Allāh need worship or a loan?

Allāh does not command to be worshipped because he needs it. Allāh is never harmed or benefited by anything. He is Al-Ghanīyy, meaning the Rich and the Self-Sufficient, and he is free of all need.

To worship Allāh only benefits the servants; it brings about a sense of purpose, peace, and well-being in this life, and even if one does not experience this contentment, then one should at least continue to worship Allāh to attain Jannah.

Any āyah (verse) of the Qurʾān or Ḥadīth that appears to suggest that Allāh has a need must be interpreted metaphorically since the Qurʾān explicitly mentions that Allāh is free of all need. For instance, the Qurʾān mentions that those who give Allāh a good loan will receive back far more from Allāh than what was given (Qurʾān 2:245). Some of the Jews in the lifetime of Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ heard this āyah and mockingly stated that Allāh is poor, while they are rich. Allāh responded to their statement.

It is therefore understood that when Allāh tests his creation by commanding them to worship him, this command was not issued due to a need that Allāh possesses.

The wisdom of the rulings of Islāmic Law, and the wisdom of sending human prophets and messengers instead of angels

Due to the nature of the test, Allāh has sent prophets to guide humanity and has revealed the Sharīʿah (Islāmic Law). As mentioned earlier, if objective morality is true, then it must be grounded in Allāh, and it cannot be based on the principle of maximizing well-being and minimizing harm because this principle is based on preference, which collapses into subjectivity. Despite this, Allāh recognizes that virtually all people prefer well-being over harm, and so the rulings of the Sharīʿah are ultimately meant to help people attain salvation, and these rulings also bring about worldly benefit by increasing overall well-being and lesser harm in this world. The reason it is said this world is because, as mentioned previously, Allāh could have created a far more merciful world wherein everyone is placed in Jannah without being tested. [5]. There is no need for a Sharīʿah in Jannah because there is no suffering therein. [6].

As for prophets and messengers, they are humans [7]. There is a difference of opinion among the ʿulamāʾ if the Jinn had prophets from among their own kind before the advent of humanity. However, there is ijmāʿ (consensus) among the ʿulamāʾ that there were only human prophets and messengers after the advent of humanity. The prophets and messengers are humans so that they can serve as role models for other humans (Qurʾān 33:21). Besides Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ, human prophets and messengers were not sent directly to the Jinn, although the Jinn would listen to their revelations (Qurʾān 46:29-30). These prophets and messengers were sent only to their own people, although they would have still have interactions with other people. As for Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ, he was sent for everyone, including the Jinn.

A question may arise: if the prophets and messengers are to serve as role models for humans, then why are the Jinn obliged to follow Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ? The answer is that despite the differences between humans and Jinn, they both have temptations and the ability to commit sin, as opposed to the malāʾikah (angels) who have no free will to disobey Allāh. Thus, the general rulings of the Sharīʿah will apply to both humans and Jinn, although there may be some specific differences. If malāʾikah were sent to be role models for people, then the people may object and say that they cannot worship Allāh because the malāʾikah do not experience temptations, nor do they have the free will to sin, nor do they have to earn a livelihood, nor do they eat or drink, and so on. Furthermore, if malāʾikah were seen in their true forms, that would defeat the purpose of the test, as almost everyone would embrace Islām after seeing them, which is why the Qurʾān mentions that people would no longer be reprieved once they see malāʾikah (Qurʾān 6:8). This is why the malāʾikah are only seen in the form of men to non-prophets in this dunyā (Qurʾān 6:9).

Why is Hell eternal?

To fail the test of Allāh is no light matter; it carries grave consequences. Those who die as kuffār will burn in Jahannam forever, yet this often raises the following question: why are people being punished forever if they only disbelieved for a finite duration? There are two answers: one is blunt, while the other is more agreeable to the masses. The first answer is that Allāh has the right to punish whomever he wills. In fact, it is within Allāh’s rights to punish individuals for eternity, even if they never committed any crime. The justification is that Allāh is Al-Khāliq (the Creator), Al-Mālik (the Owner), Al-Malik (the King), and Ar-Rabb (the Sustainer) of all of creation. Since he owns everything, then he has the right to do anything. Indeed, only those who have reached the pinnacle of taslīm (submission) will accept this. Naturally, some may reject this justification.

The second answer is that the duration and severity of the punishment of Jahannam is in accordance with the duration and severity of the crimes committed by the kuffār. The crime that specifically condemns one to eternal damnation is shirk (Qurʾān 4:48). Shirk is essentially idolatry or polytheism, but to define it more thoroughly, shirk is to associate partners with Allāh by giving what is exclusively due to Allāh to other than him [8]. The Qurʾān mentions that Allāh forgives all sins, and this would include shirk (Qurʾān 39:53). However, it also mentions that tawbah (repentance) is not accepted from the one who persists in sin and then repents upon death (Qurʾān 4:18). Thus, the correct understanding of Qurʾān 39:53 is that Allāh forgives all sins, so as long as a person repents before death, but those who die without repenting from shirk are doomed forever.

The duration of the punishment of Jahannam for the kuffār is everlasting, yet they only disbelieved for a finite portion in the dunyā. The reason that they are punished perpetually is because had they lived forever in the dunyā, they would have disbelieved forever.

As for the severity of the punishment of Jahannam for the kuffār, it increases every moment to no end. The reason for this is because the kuffār would have disbelieved forever, and every moment wherein they disbelieve is further accumulation of sin. The more one sins, the greater the punishment. Additionally, the following question can be made to understand the severity of shirk: should a person who murders a fellow human being receive more punishment than a person who kills a plant? Most people would answer in the affirmative because they judge humans to be greater than plants; humans have greater attributes than plants, such as greater power and knowledge. Thus, to violate a human would be far worse than to violate a plant. If so, then it is fitting that the punishment for an individual who violates an infinite being should be infinite. Those who die as disbelievers will be perpetually punished with torment that never ceases to worsen because their crime was infinite in duration and in severity. It can be anticipated that a person may disagree by not considering shirk to be a crime in the first place, but it is Allāh who considers it a crime, and that is sufficient for the matter.

Why did Allāh create people whom he knew would enter Hell? The falsity of the Christian position that God loves those in Hell

A common question is that even if Allāh wanted to test his creation and gave people free will, why create people whom he knew would fail the test? Why not create people who only pass the test? Why did Allāh create people whom he knew would enter Jahannam? The mainstream view among Christians is that God is all-loving and that he even loves those whom he condemns to burn in hell forever. Christians typically respond that although God loves everyone, it is up to people to accept his gift of salvation. By rejecting this gift, people have essentially chosen to reject God’s love, so God loves them, but they do not love him, or at the very least, they do not love him sincerely. This is a semi-reasonable response, but it contains a contradiction. Islām and Christianity both teach that people will end up in Jahannam because they failed to use their free will properly in order to attain salvation. However, both religions teach that Allāh created many people knowing in advance that they would burn in Jahannam for eternity. A syllogism demonstrates the falsity of the mainstream Christian position.

- It is not loving to create many people knowing in advance that they would burn in Jahannam forever.

- Allāh has created many people knowing in advance that they would burn in Jahannam forever.

- Therefore, Allāh is not all-loving.

This syllogism is valid. The first premise is agreed upon by Christians and Muslims. Of course, many people reject the first premise. The doctrine of Jahannam cannot be known to be true using pure logic alone. The only way to know if it is true is through revelation or if one saw it. The Qurʾān is a true revelation due to the proofs and evidences it presents, such as prophecies and miracles. Once one accepts the Qurʾān as true revelation, then one can be certain that Jahannam is real, even without witnessing it. The second premise is obviously true because it is not loving to create people knowing in advance that they would burn in Jahannam forever. It would have been more loving to not create those who are destined for everlasting anguish. Those who say otherwise must demonstrate how this is loving. If the first two premises are true, then the conclusion must be true: Allāh is not all-loving, and so the mainstream Christian position is false. It does not matter if one says that the people of Jahannam ended up in Jahannam due to their failure to acquire salvation because it was not necessary for Allāh to create them in the first place.

As for Islām, the question of why does Allāh create people whom he knew would enter Jahannam is not problematic, just as the problem of suffering is not problematic because Islām does not teach that Allāh is all-merciful or all-loving. In fact, Allāh hates kufr (disbelief), shirk (polytheism and idolatry), and the people of kufr and shirk who die without tawbah (repentance). He is angry with them and does not love them, and so it would make sense to create them.

Is Allāh obligated to do what is best for his creation?

Clearly, Allāh does not always do what is best for all of his creation, for if he did do what was best for everyone, then he would have placed everyone in Jannah without testing them or at the very least, he would not have created those whom he knew would fail his test. Imām Al-Ashʿarī, a former Muʿtazilī of the past who became a major Sunnī theologian, stumped his former Muʿtazilī teacher Al-Jubbāʾī on this topic of discussion. He showed his former teacher that Allāh is not obligated to do what is best for creation, as opposed to the Muʿtazilah who believed that Allāh always does what is best for his creation and that he is obligated to do so. Imām Al-Ashʿarī mentioned a parable of three brothers: one who died as a believer and entered Jannah, one who died as a child and entered a lower level of Jannah, and one who died as a kāfir (disbeliever) and entered Jahannam. Imām Al-Ashʿarī asked Al-Jubbāʾī why does the child enter a lower level in Jannah, to which he replied that the believer lived longer, did more righteous deeds, and underwent more struggles, while the child did not live long enough to struggle and do more good deeds. Imām Al-Ashʿarī asked what if the child tells Allāh on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Judgement Day) that had he grown up, he would have done more good deeds. Al-Jubbāʾī replied that Allāh would tell him that he took his life as a child because he knew that had the child grown up, he would have become a sinner or a kāfir. Imām Al-Ashʿarī asked why then did Allāh not take the life of the kāfir as a child so that he did not grow up to become a kāfir in the first place, to which Al-Jubbāʾī was unable to answer coherently. This discussion was one of the reasons why Imām Al-Ashʿarī abandoned the Muʿtazilah and became a Sunnī. Sunnī ʿaqīdah (creed) teaches that Allāh is not obligated to do what is best for his servants, but he does whatever he wills.

If Allāh is omniscient, why test anyone?

One may be curious and ask that if Allāh is omniscient, then why test anyone? Why not just place people into Jahannam or Jannah if Allāh already knows what each individual would have done? The answer is that while virtually everyone would not mind being placed into Jannah without being tested, those who enter Jahannam would certainly like to know why they are being punished. People undergo the test so that they can witness their own deeds (Qurʾān 75:14).

Those who attempt to deny the accuracy of their book of deeds on Yawm al-Qiyāmah will have their mouths sealed, and their own hands and feet will testify against themselves (Qurʾān 36:65).

Allāh's mercy exceeds his wrath

A Ḥadīth mentions that Allāh’s mercy surpasses his wrath.

Abū Hurayrah reported: The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ said, "When Allāh completed the creation, he wrote in his book that is with him above the throne: Verily, my mercy prevails over my wrath" (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 3194).

Allāh has no limit to how much mercy or wrath he can show, but he shows more mercy than wrath. He has made it far easier to earn good deeds than to earn sins. When one accepts Islām, all previous sins are forgiven and erased in one's book of deeds, while one's good deeds remain, and it is possible that one's previous sins will be recorded as good deeds. If the practice of Islām is sincere, Allāh will reward each good deed 10 to 700 times. As for the sins performed after becoming Muslim, each evil deed will only be recorded as one evil deed, unless if Allāh forgives it [9].

Additionally, Jannah will have more inhabitants than Jahannam. A Ḥadīth reports that out of every 1,000 humans, 999 of them are destined for Jahannam. However, most of these individuals who are destined for Jahannam are from the tribes of Yāʾjūj (Gog) and Māʾjūj (Magog) (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 222). Moreover, Jannah is far more expansive compared to Jahannam. The location of Jahannam is said to be within the earth, while Jannah is in the seventh samāʾ (heaven) or is above the seven samāwāt (heavens) altogether, and Jannah is said to be as wide as the samāwāt and earth (Qurʾān 3:133). Jahannam will be filled with multitudes, and it will ask for more people to be filled, but Allāh will place his qadam in it, and Jahannam will shout, "Enough, enough!". As for Jannah, it will be filled with multitudes as well, but much space will remain, so Allāh will create people to fill this space (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2848c) [10]. This demonstrates that Allāh will create new creation to fill Jannah after humans have entered it, and since Jannah is larger than Jahannam, then this means that the number of those destined for Jannah is greater than the number of individuals destined for Jahannam, and this demonstrates that Allāh's mercy excels his wrath.

The compensation for suffering in the hereafter makes suffering worthwhile

It is natural for humans to complain about suffering. Even Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ would complain at times when he was in pain (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 5648). However, a hardship should never make a person disbelieve or disobey Allāh. As for the kāfir who lived the most pleasant life in the dunyā, he will be dipped once in Jahannam, and he will utterly forget the pleasures he experienced in this life. As for the believer who lived the most troublesome life in the dunyā, he will be dipped once in Jannah, and he will utterly forget the hardships he experienced in this life (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2807). Jannah makes suffering worthwhile. Indeed, those believers who suffered in this world will be compensated to such an extent in the ākhirah (hereafter) that other people will wish they suffered more so that they could reap the rewards of those who suffered. This should behoove a person to believe and to endure suffering patiently in order to attain these rewards.

Jābir reported: The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ said, "The people who lived in prosperity will wish on the Day of Resurrection to have the reward of those who were put to trial, even if their skin had been torn away with shears" (Jāmiʿ At-Tirmidhī 2402).

People chose to be tested

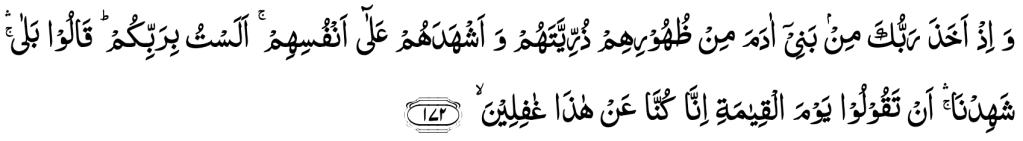

A critic may say that even if those who suffer will be granted compensation, they did not choose to be created and tested. This is actually untrue; there is a world known as ʿālam al-arwāḥ (the realm of souls) that came before the dunyā, and in this realm, humans chose to be tested before their souls were placed in their bodies in the dunyā. Allāh offered the heavens and the earth, including the mountains, the choice to take the test. If they succeeded, they would be given the best reward, but if they failed, they would face the worst punishment. They were fearful and refused. Allāh had also created Prophet Ādam, the progenitor of humanity, and gave him the choice to take the test, and he accepted. Those beings whose spirits accepted this trust later had their spirits placed in human bodies in the wombs of their mothers, with the exception of Ādam and his wife who were born without any parents.

If people censure Allāh for testing them, then why did they voluntarily agree to take the test? If they say that they do not remember this covenant that Allāh made with them, then they should know that the Qurʾān has reminded them of their covenant, and the Qurʾān is certainly true because of its numerous proofs and evidences that indicate that it is from Allāh [12].

Explanation of suffering not caused by moral agents. Suffering is not always due to one's sins

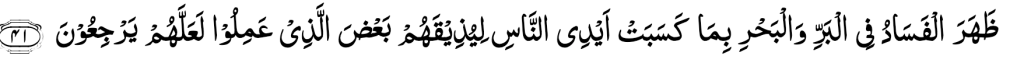

The main reason for suffering is that Allāh has chosen to test some of his creation and has given them free will. As a result, people commit all sorts of atrocities against each other. However, a lot of suffering is not always a result of humans. Sometimes suffering comes about due to natural events, such as natural disasters, diseases, famine, and so on. Since Allāh is the Creator of everything, then he is the moral agent directly responsible for suffering that comes about due to natural events since he created those events. Why would he create suffering that comes about due to natural events?

The response is that it is an assumption to assume that humans have nothing to do with these natural events. Many human activities can lead to many natural disasters and harmful circumstances, such as disease outbreak, climate change, pollution, waste buildup, dust storms, landslides, wildfires, and even earthquakes. Other animals can also contribute to such events, though typically on a much smaller scale than humans. Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that the Jinn also perform activities that lead to these disasters. One may still object and say that there could be natural disasters that do not come about due to created beings, so why would Allāh cause these events?

There are many reasons for why Allāh would choose to create these events. Allāh may punish people for their sins using natural disasters.

While suffering may serve as a punishment, suffering is not always due to sin. Suffering may remind a person of the punishment of the ākhirah (hereafter) so that they take heed and repent. A person’s sins may be expiated because of suffering, and a person’s rank may increase in the sight of Allāh.

ʿĀʾishah reported: The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ said, "No believer is pricked by a thorn or more but that Allāh will raise him a degree in status or erase a sin" (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 5640).

As mentioned earlier, the people in the ākhirah will wish that they suffered more in the dunyā so that they could attain the rewards of those believers who bore their suffering gracefully. However, some people do not experience much suffering in this life, so how can they attain these rewards? The answer is that if a person experiences ease and is grateful to Allāh, then they can attain the same reward of a person who experiences hardship and is patient.

Abū Hurayrah reported: The Prophet ﷺ said, "The one who eats gratefully has the status of one who fasts patiently" (Jāmiʿ At-Tirmidhī 2486).

People should not let the state of ease fool them. To experience ease may be a more difficult test than to suffer. A rich person may be corrupted by his wealth, whereas a poor person may be made humble due to his poverty, yet it is also possible that a rich person is grateful to Allāh for his wealth and utilizes it properly, while a poor person may disbelieve in Allāh due to his difficult circumstances. The pristine believer is one who worships Allāh whether in a state of hardship or ease.

Animal suffering

All creatures of the earth will be resurrected and judged on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Judgement Day) [13]. Animals will settle their disputes with one another (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2582). Even if a human or one of the Jinn wronged an animal, then this animal will receive justice. Indeed, a Ḥadīth mentions that a woman will be thrown into Jahannam for unnecessarily caging a cat, and she did not feed it or quench it leading to its death (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2619). Despite all of this, will not the suffering of these animals be in vain since it is known in Islām that they will turn into dust after judgement?

It is true that all creatures of the earth will settle their scores after being judged. Once their scores have been settled, then all of them will become dust. When the kāfir sees this, he will wish he was turned into dust to escape his fate of eternal damnation, and this is the meaning of the āyah (verse):

The benefit of turning into dust is that no creature of the earth will be punished in Jahannam. There are animals in Jahannam that were created to punish the inhabitants therein, but these animals do not suffer, nor are they the same animals from earth. Similarly, there are animals in Jannah that are not originally from earth that were created to reward the inhabitants therein. These animals may be used for various purposes, such as transport, but some of them are eaten by the people of Jannah, but they do not suffer from this because they are slaughtered and cooked instantly, and then they are recreated to roam about again.

Ibn ʿAbbās said, "The people of the Garden will desire a bird, and it will fall before them roasted as they used to eat it in the world. When they finish eating, it will fly away as it was" (al-Suyūṭī, al-Durr al-Manthūr fī al-Tafsīr bi’l-Maʾthūr, 8:77).

As for the animals of the earth that will be turned into dust, any suffering that traumatized them will be forgotten when they are dead. However, it is also possible that they enter Jannah because some Aḥādīth mention that particular animals will be in Jannah. One example of this are sheep.

Abū Hurayrah narrated: The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ said, "Pray in the sheep pens and wipe their dust, for they are among the animals of the Garden" (Al-Bayhaqi 2:449).

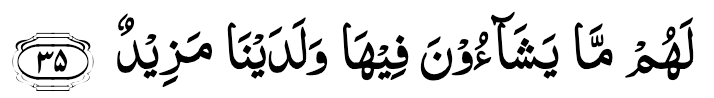

Still, it is possible that these sheep that are in Jannah are not the same sheep of the earth. Nevertheless, what is clear from Islāmic sources is that the people of Jannah will have all that they ask for, so if they desire for the animals of the earth to enter Jannah, then Allāh will resurrect them and gather them into Jannah.

While the people of Jannah will receive what they desire, the question is will they desire for the animals of the earth to enter Jannah? This is unknown because the psychology of the people of Jannah will be different, but it is hoped that the animals of the earth enter Jannah after they have been turned into dust. Even if they are to remain nonexistent forever, at the very least, they will not be punished in Jahannam, and this is a better fate than that of the kuffār, and Allāh is free to do with his creation and property as he wills.

Response to those who say that they are more merciful than Allāh

Some individuals claim that they are more merciful than Allāh. The question is on what grounds do they make this claims? Can they provide for all of Allāh’s creation? If they answer no, then they must admit that Allāh is more merciful than them. People disbelieve in Allāh, and he still allows them to eat, drink, sleep, procreate, and so on. Humans cannot enumerate the blessings that Allāh provided for all of his creation, from the tiniest cell to the largest creatures, all of them are under the care of Allāh. On earth alone, there are approximately 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 living cells. People may respond by saying that they cannot provide for all of creation because they lack power, but they may claim that if they were Allāh, then they would create a world free of suffering and that they would have placed everyone into Jannah without any need of a test. The response to this is that they do not have the station of Allāh, nor can they ever attain the position of Allāh, and so they should cease making empty claims that cannot be verified. Such claims are ultimately futile and will not benefit them in the least in the ākhirah.

Salvation is attained through Allāh's mercy and not through one's faith or good deeds

Let not a person be beguiled; it is not through one’s good deeds or one’s īmān (faith) that one attains salvation. Certainly, a believer will be granted Jannah due to his īmān, but one should know that Allāh is not obligated to reward anyone for anything. When citizens obeys the law, should they be rewarded? Of course not; they are supposed to obey the law regardless. They should only be punished if they break the law. It is a mercy from Allāh that he rewards people for simply doing what they are obligated to do. Thus, it is ultimately due to the grace of Allāh that a person attains Jannah.

Jābir reported: The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ said, "None of you will enter the Garden by his good deeds alone, nor would you be rescued from Hell, including myself, but it is due to the grace of Allāh" (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2817).

[1] It is important to distinguish the moral use of the word good from its use in everyday language to indicate well-being or benefit. For example, when a person says, "I feel good," what is meant by this is that they are in a state of well-being. When a person says, "It is good to eat healthy," what is meant by this is that it is beneficial to eat healthy. This is different from making a moral claim by judging something to be morally good.

[2] Of course, it is correct to say that it is objectively true that some people find the taste of chocolate ice cream to be subjectively better than vanilla ice cream.

[3] Allāh has unlimited names, ninety-nine of which are the most popular. Some of these names are often mistranslated, such as Ar-Raḥmān being translated as the All-Merciful, Al-Wadūd being translated as the All-Loving, Al-Ghafūr being translated as the All-Forgiving, and so on. It is more accurate to translate these names as Most Merciful, Most Loving, and Most Forgiving. It is misleading to use 'all' as a prefix for these names because some people would understand this to mean that Allāh shows absolute mercy, love, and forgiveness to everyone, and this is not a teaching of Islām. However, it is fine to say that Allāh is all-knowing and all-powerful.

[4] In Islām, a believer is not merely one who knows that Allāh exists and that Islām is true, otherwise Shayṭān would be a believer, rather, there is more required in order to be considered a believer.

[5] Allāh has generously permitted many of his creation to abide in Jannah without having to undergo any test, but the reward of these beings are far less than the reward of those who are tested and win Jannah, such as the believers among Jinn and humanity.

[6] When people hear about the Sharīʿah, they often think about its penal code, but the Islāmic penal code is only a small part of the Sharīʿah. The main goal of the Sharīʿah is to help people earn the pleasure of Allāh, as a result of which they are made to enter Jannah. In relation to this worldly life (dunyā), the objectives of the Sharīʿah (maqāṣid ash-Sharīʿah) are mainly meant to promote well-being and to minimize harm by protecting and preserving five aspects: religion, life, intellect, lineage, and property. Virtually every aspect of daily living will fall into one or more of these categories.

[7] There are differences between prophets and messengers, but this is not the place to mention these differences in detail. All messengers are prophets, but not all prophets are messengers.

[8] Kufr (disbelief) is often used interchangeably with the term shirk in the Qurʾān; kufr is shirk, and shirk is kufr, but these terms each have a specific and distinct definition when mentioned together. Kufr is to reject an aspect of the religion or to exhibit arrogance or mockery towards it. Kufr is of many types, but it has two main types: kufr akbar (major disbelief) and kufr asghar (minor disbelief). The former is to reject or to exhibit arrogance or mockery towards a major aspect of the religion, and it is this type of kufr that expels one from the religion, while the latter pertains to similar attitudes towards less critical aspects and does not expel a person from the religion. Shirk, like kufr, has many types but is also mainly divided into two types: shirk akbar (major idolatry) and shirk asghar (minor idolatry). The former expels one from the religion, while the latter does not. Shirk akbar and kufr akbar both condemn a person to eternal damnation. In scholarly works, when kufr or shirk is mentioned without specification of type, it usually refers to kufr akbar and shirk akbar, although this is not always the case.

[9] Even though Allāh forgives new Muslims for their past sins, Muslims may still be punished in a Muslim country for certain crimes committed before accepting Islām, so it is unwise to assume that embracing Islām will certainly make one escape prosecution.

[10] Qadam literally means foot, but when this word is used in reference to Allāh, then it does not denote a physical limb or body part.

[11] Those whom this āyah (verse) labels as unjust and ignorant are the ones from among humanity who will fail to fulfill this trust, such as the kuffār (disbelievers) who are the majority of humanity.

[12] Some Muslims have claimed to remember this covenant, but personal memory is not sufficient enough to be a proof that this covenant is true. Rather, the covenant is known to be true because the Qurʾān affirms it.

[13] Malāʾikah will not be judged on Yawm al-Qiyāmah because they are not tested as they do not experience temptations and have no ability to sin.

[14] The people of Jannah will have all that they desire and a bonus. This bonus is the beatific vision, which refers to the believers being blessed to see Allāh, and this is the greatest reward in Jannah. The worst punishment in Jahannam is that the kuffār will never see Allāh.

Leave a comment