Does Allāh have a body?

As demonstrated in a previous article, God must be immaterial. Many āyāt (verses) of the Qurʾān appear to describe Allāh (God) using human-like or physical descriptions. For example, the Qurʾān mentions that Allāh has a wajh (Qurʾān 2:115), ʿuyūn (Qurʾān 23:27), yadayn (Qurʾān 38:75), and even a sāq (Qurʾān 68:42). Wajh literally means face, ʿuyūn literally means eyes, yadayn literally means two hands, and sāq literally means shin. Similarly, numerous Aḥādīth contain seemingly corporeal or anthropomorphic descriptions. This raises an important question: how can these references be understood in light of the belief that Allāh is immaterial? The answer is that the Qurʾān itself offers guidance on how to understand these seemingly physical descriptions.

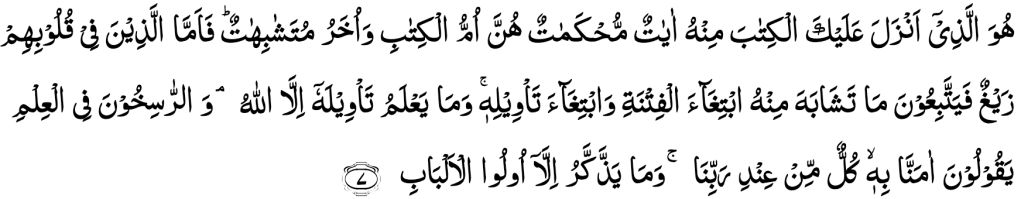

Qurʾān 3:7 explains that some āyāt are clear and straightforward, while others are ambiguous. The Qurʾān advises people to focus on the clear āyāt and not to be preoccupied with the ambiguous ones, as the absolute reality of these āyāt can only be known by Allāh. As for the seemingly anthropomorphic or corporeal descriptions found in the Qurʾān or in the Aḥādīth, these are considered ambiguous because the Qurʾān states that nothing resembles Allāh (Qurʾān 42:11). It seems strange that the Qurʾān attributes a wajh, ʿuyūn, yadayn, and a sāq to Allāh, while simultaneously stating that nothing resembles Allāh. This ambiguity raises the question on how should these references be interpreted.

There were people who understood these references in a corporeal sense and believed that Allāh had a jism (body). This view is problematic because the Qurʾān says that nothing resembles him, but bodies are practically everywhere within creation, and so it follows that Allāh cannot be a body. Some might attempt to address this by suggesting that Allāh could have a body that is unlike any other body. However, this is not an adequate response, as it implies a difference in degree rather than a fundamental difference in kind. More importantly, this view contradicts the absolute oneness and indivisibility of Allāh that is mentioned in the Qurʾān because a body is composed of parts. Additionally, the earliest Muslims did not hold to this conception of Allāh.

The mufassir (exegete) Ibn Kathīr mentions how the earliest Muslims usually approached the ambiguous references mentioned in the Qurʾān or in the Ḥadīth corpus using tafwīḍh.

"…people have many positions on this matter, and this is not the place to present them at length. On this point, we follow the position of the early Muslims (Salaf): Mālik, Al-Awzāʿī, Ath-Thawrī, Al-Layth bin Saʿad, Ash-Shāfiʿī, Aḥmad, Isḥāq ibn Rāhwayh, as well as others among the Imāms of the Muslims, (of) ancient and modern (times), which is to let the verse pass as it has come, without modality, without any resemblance to created things, and without nullifying it, and the apparent meaning that comes to the minds of al-mushabbihīn (those who liken Allāh to his creation) is negated of Allāh, for nothing created has any resemblance to Him: There is nothing like him, and he is the All-Hearing, the All-Seeing (Qurʾān 42:11)" (Tafsīr Ibn Kathīr 85).

Tafwīḍh is to consign the true reality of such expressions entirely to Allāh without attempting to interpret them, while simultaneously negating any resemblance between Allāh and his creatures (tashbīh) or corporeality (tajsīm), and this was the approach of the Ḥanbalī madhhab (school). For example, when the Qurʾān mentions the yadayn of Allāh, the Ḥanābilah would affirm the word without assigning a specific interpretation, leaving its reality to Allāh alone, while at the same time denying that yadayn means physical body parts. Many languages, including Arabic, often use the same word to convey entirely different meanings depending on context. For example, the word ‘hand’, when used in reference to a human limb, has a completely different meaning compared to when the word ‘hand’ is used in reference to a clock. Similarly, when the Qurʾān mentions the yadayn of Allāh, it must be understood that its reality is different and shares no similarity with creation.

Within the Ḥanbalī tradition, there emerged various strands that utilized tafwīḍh in different ways. The Ashʿarī and Māturīdī schools also utilized tafwīḍh, but they made use of taʾwīl as well. Taʾwīl is to assign a metaphorical meaning to a particular reference in a way that is compatible with the Arabic language. For instance, when the Qurʾān refers to the yadayn of Allāh, this may be interpreted to symbolize divine power or strength instead of physical hands [1]. Some of the earliest Muslims also engaged in taʾwīl, including Ibn ʿAbbās رضي الله عنه, a ṣaḥābī (companion) and cousin of Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ. For example, Qurʾān 68:42 states that Allāh will uncover the sāq on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (the Day of Judgement), and people will be commanded to prostrate, though many will be unable to do so. Ibn ʿAbbās رضي الله عنه interpreted this phrase metaphorically, explaining that the uncovering of the sāq refers to the intense direness and distress on Judgement Day and that it does not mean that Allāh has a physical shin that people will prostate towards (Al-Mustadrak ʿAlā aṣ-Ṣaḥīḥayn 2:499-500). This interpretation is rooted in classical Arabic usage; in ancient Arab culture, uncovering the shin was associated with stressful events. For example, when preparing for battle or moving quickly through the desert, people would lift their garments, exposing their shins. As a result, the expression became a metaphor for difficulties.

The Ḥanābilah typically discouraged the use of taʾwīl, unless it could be shown that the Prophet ﷺ or his Ṣaḥābah (companions) had applied it in a particular instance. Nonetheless, tafwīḍh has historically been more widely adopted in Sunnī Islam compared to taʾwīl, as it is considered a safer approach. By avoiding interpretation altogether, it minimizes the risk of misrepresenting what is meant by such ambiguous expressions. Still, many ʿulamāʾ (Islāmic scholars) turned to taʾwīl when they felt that people would not be content with leaving an expression uninterpreted. Nevertheless, whether one adopts the approach of tafwīḍh or taʾwīl, there is a consistent principle upheld across all Sunnī madhāhib (schools): any reference that appears to attribute limbs or physical parts to Allāh must never be understood in a bodily manner. Thus, the appropriate way to approach these ambiguous references is either through tafwīḍh or through taʾwīl, while denying any corporeality for Allāh.

Does Allāh have a waist, loin, a lower garment, or a loincloth?

A Ḥadīth states that after Allāh created creation, the womb clung to the ḥiqw of Allāh (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 4830). In Arabic, the word 'ḥiqw' can refer to the waist or loin. However, since Allāh does not possess a physical body, ʿulamā may apply tafwīḍh and consign the true reality of this word to Allāh, while simultaneously rejecting any anthropomorphic or bodily interpretation of the term. As for ta'wīl, the Arabs used to use the expression, "he caught hold of his waist," in order to mean that someone has sought another for help, protection, or refuge (As-Silsilah aṣ-Ṣaḥīḥah 1602). This expression does not literally mean that a person is actually clinging on to someone's waist. In the Ḥadīth mentioned prior, the context is that the womb sought Allāh's protection against those who cut off the ties of kinship. Allāh asked the womb if it will be pleased if he bestows his favors upon those who maintain these ties and withholds favors from those who break these ties. The womb replied in the affirmative.

Another Ḥadīth refers to the izār of Allāh, which is a lower garment or loincloth wrapped around the waist. This Ḥadīth states that Allāh said that his cloak is his grandeur and that his izār is his magnificence (Sunan Abī Dāwūd 4090). It is obvious from this report that the izār of Allāh is not a literal garment that covers the body. This further reinforces the understanding that Allāh does not have a physical waist or loin.

Does Allāh have a shape, form, or image?

It is alleged that Islām teaches that Allāh has a physical shape because a Ḥadīth mentions that Allāh will reveal himself to believers on Yawm al-Qiyāmah in a particular ṣūrah (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 6573). The Arabic word ṣūrah, not to be confused with the word sūrah (chapter), can mean a shape, image, or form. The response to this allegation is that the word ṣūrah can be used for anything that can be visualized, even if what is visualized is not actually physical, such as what is visualized in dreams or thoughts. Therefore, Allāh can make himself seen in a specific ‘ṣūrah‘ without necessitating corporeality.

In another Ḥadīth, Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ mentions that he had a dream where he saw Allāh in the best ṣūrah. He said that Allāh asked him a question thrice, but he did not know the answer, and then he felt Allāh place his kaff between his shoulders and that he felt the coolness of his anāmil. After this, he had the knowledge to answer Allāh’s questions (Jāmiʿ at-Tirmidhī 3235). Kaff literally means palm, and anāmil literally means fingertips. As mentioned earlier, the earliest Muslims would affirm these wordings but would utilize tafwīḍh and consign their realities to Allāh. Others would utilize taʾwīl and metaphorically interpret these words to mean that Allāh placing his kaff between the shoulders of Muḥammad ﷺ indicates Allāh bestowing knowledge upon Muḥammad ﷺ. In either case, no Muslim would believe these wordings signify that Allāh has body parts that resemble creation.

Does Allāh have the form of a young beardless man with curly hair?

There is a report that mentions that the Prophet ﷺ saw Allāh in the ṣūrah of a young beardless man with curly hair in a dream (Bayān Talbīs al-Jahmīyyah 7:294). The overwhelming majority of muḥaddithūn (Ḥadīth scholars) have either declared this report to be an outright fabrication or very weak in its authenticity [2]. Even if the report was authentic, it mentions that such an appearance was seen in a dream. How one sees Allāh in a dream does not necessarily correspond to reality. Nevertheless, the fact that this report has been declared as a fabrication by most muḥaddithūn is sufficient to refute the notion that Islām teaches that Allāh has the form of a man.

Did Allāh create Ādam عليه السلام in his image?

Islām teaches that people should try to avoid striking the faces of others, even during a fight, unless if necessary. This is because a Ḥadīth states that if a Muslim were to fight his fellow brother, then he should avoid striking his face because Allāh created Ādam عليه السلام, the progenitor of humanity, in his image (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2612). Some allege that this Ḥadīth demonstrates that Allāh resembles humans in their appearance. The response is that what is meant by ‘his image’ does not refer to Allāh but refers to Ādam عليه السلام. The explanation of this is that Ādam عليه السلام was created directly as an adult and did not undergo childhood development, and so it is said that Allāh created him in the image he had as an adult. Others have said that ‘his image’ refers to the brother that one is fighting; that is, one should avoid striking another’s face because of the resemblance humans share with their progenitor. Even if ‘his image’ refers to Allāh, then the ʿulamāʾ have mentioned that what this could mean is that just as humans have attributes such as hearing, sight, knowledge, and power, so too does Allāh possess such attributes. However, his attributes are necessary and absolute, while the attributes of humans are contingent and limited. Indeed, none of the earliest Muslims ever understood this Ḥadīth to mean that Allāh has a physical body resembling humans.

Is Allāh light?

Qurʾān 24:35 says that Allāh is the light of the samāwāt (heavens) and the earth. This has been interpreted to mean that Allāh is the ultimate source of truth and guidance. In fact, other āyāt of the Qurʾān use the word 'light' to refer to guidance and not necessarily the physical light that humans are accustomed to seeing (Qurʾān 6:122). Light in the literal sense is electromagnetic radiation that exists within space, and depending on the spectrum, some light is visible to humans. Since light requires space to exist, it is physical, but since it is not matter and has no mass, it is not material. As for Allāh, he transcends space, so he is neither physical nor material. Thus, when it is said that Allāh is light, taʾwīl may be used to metaphorically interpret this to mean that Allāh is the ultimate source of truth and guidance, or one may use tafwīḍh and consign the reality of Allāh's light to Allāh without delving into interpretation, while simultaneously denying that Allāh is actually composed of physical light that exists within space. Some may allege that Islām does portray Allāh as composed of a physical light because the Ḥadīth corpus mentions that when Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ was asked if he saw Allāh during al-Isrāʾ wa al-Miʿrāj (the Night Journey and the Ascension), he replied that he saw light (Jāmiʿ At-Tirmidhī 3282). However, multiple Aḥādīth specify that the light he saw was the light from the veil of Allāh (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 179b) [3].

Will Allāh be seen?

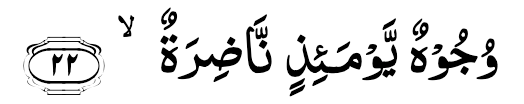

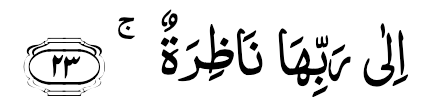

According to Sunnī Islām, Allāh will be seen by believers in the ākhirah (hereafter). The beatific vision is explicitly affirmed by the Qurʾān.

However, other āyāt (verses) of the Qurʾān seem to suggest that Allāh cannot be seen, which is one reason why heterodox sects did not affirm the beatific vision. For example, Qurʾān 6:103 says that no vision can encompass Allāh, while Allāh encompasses all vision. Additionally, Mūsā (Moses) عليه السلام asked to see Allāh, but Allāh told him that he will never see him (Qurʾān 7:143). The response is that Qurʾān 6:103 only negates an absolutely encompassing vision of Allāh. Imām Aṭ-Ṭaḥāwī رحمه الله, who authored a work on the ʿaqīdah (creed) of the earliest Muslims, mentioned that the beatific vision will not be all-encompassing.

The vision of the people of Jannah (the Garden) is true, without being all-encompassing and without modality (Al-ʿAqīdah Aṭ-Ṭaḥāwīyyah).

As for Qurʾān 7:143, Allāh says to Mūsā عليه السلام, “lan tarānī,” which means you will never see me. The particle ‘lan‘ is used for negation of the future. The response is that this particle is used for emphatic negation of the future but does not always imply an absolute negation. For instance, Qurʾān 2:95 uses this particle and mentions that some kuffār (disbelievers) will never wish for death. However, Qurʾān 43:77 states that all kuffār will beg for death when they are in Jahannam (Hell). This demonstrates that the particle ‘lan‘ does not necessitate absolute negation of the future.

As for the Ḥadīth corpus, there are numerous reports that mention that Allāh will be seen by the believers.

Jarīr رضي الله عنه narrated: Allāh's Messenger ﷺ came out to us on the night of the full moon and said, "You will see your Sustainer just as you see this moon. There will be no crowd to block your sight..." (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 554) [4].

The explicit references of the Qurʾān and Ḥadīth corpus, as well as the view of the early Muslims, validates the Sunnī claim that belief in the beatific vision of Allāh is a correct Islāmic doctrine, as opposed to heterodox sects that opposed this claim.

Does believing that Allāh can be seen necessitate corporeality?

An objection that may be raised is that everything that is seen is a physical body. Since Allāh is not a body, he cannot be seen. Therefore, any āyah (verse) or Ḥadīth that suggests otherwise must be reinterpreted, and this is another reason why heterodox sects did not accept the beatific vision. The answer to this objection is that this argument is based on the assumption that everything that can be seen must be a body simply because everything a person has seen happens to be corporeal; this is an inductive fallacy. The objector may say that sight involves light rays reflecting off an object and entering the eye. Therefore, anything that is seen must have a surface for light to reflect from, which implies that it must be a physical body.

The response is that the reflection of light and its entry into the eye are preceding events that usually result in sight, but these events are not identical to the act of seeing itself. A person can still see clear and vivid images in the mind, even if one’s eyelids are shut; such images can be seen in dream and in thoughts. Dreams and thoughts require material processes, such as brain activity, to occur, but dreams and thoughts are not themselves material. Once this distinction is made clear, it follows that what is seen does not necessarily have to be a body because the use of light is not a necessary condition for sight. Allāh can create the act of seeing in the eyes of the believers, by which they will come to know him in a more profound way. Since this vision does not depend on light, it does not necessitate that he is corporeal in any way.

Does Allāh laugh?

Since Allāh is immaterial, one should not imagine his kalām (speech) as being produced by vocal cords. Indeed, Allāh can communicate without the need for bodily instruments, just as he possesses consciousness and will without a nervous system. Relatedly, a Ḥadīth mentions that Allāh laughs at the despair of his servant because he will soon relieve him (Sunan Ibn Mājah 181). No Muslim believes that Allāh’s laughter involves sounds produced by vocal cords or physical movements such as diaphragm contractions. Instead, ʿulamāʾ either apply tafwīḍh, consigning the reality of this laughter to Allāh, while rejecting any anthropomorphic or corporeal implications, or they use taʾwīl to interpret it metaphorically. For example, Imām Al-Bukhārī explained that the ‘laughter’ of Allāh is divine mercy (Al-Asmāʾ wa aṣ-Ṣifāt 643).

Does Allāh move?

The Qurʾān and the Ḥadīth corpus describe Allāh as descending, coming, and running. As mentioned in a previous article concerning the immateriality of necessary existence, Allāh does not exist within space, so it is incorrect to attribute physical movement to him. Movement implies spatial confinement and change of position from one place to another, while Allāh is the creator of place and is not contained within his creation. It is equally incorrect to describe Allāh as stationary, since being stationary is to remain fixed in one location. Allāh exists without place, so it is a category error to attribute movement or immobility to him.

Those who adopt the method of tafwīḍh consign the true reality of these descriptions to Allāh, while firmly denying that such expressions imply spatial confinement. They affirm that nothing contains Allāh and that he is utterly transcendent beyond all spatial dimensions. Those who utilize taʾwīl for these references will interpret them metaphorically in a manner compatible with the Arabic language. For instance, the Qurʾān states that Allāh will come (Qurʾān 2:210). Those who favor taʾwīl do not interpret this as a literal movement of Allāh through space but as a figurative expression instead. It is reported that Imām Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal interpreted this āyah to mean that the recompense of Allāh will come (Al-Bidāyah wa an-Nihāyah 10:342).

Regarding the descent of Allāh, a well-known Ḥadīth states that Allāh descends during the last third of the night and asks, “Who is seeking my forgiveness so that I may forgive them?” (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 758). Many ʿulamāʾ have interpreted this descent metaphorically, explaining that it refers to the descent of Allāh’s mercy to those who seek him during this blessed time. Similarly, another Ḥadīth states, “If a person walks to Allāh, Allāh will run to him” (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2687). This is understood to mean that if someone makes an effort to draw closer to Allāh through righteousness, Allāh will respond with even greater mercy, forgiveness, and acceptance.

Does Allāh experience shyness?

A Ḥadīth mentions that Allāh is shy to turn away a supplicant empty handed.

Salmān al-Fārisī رضي الله عنه reported the Prophet ﷺ said. "Verily, Allāh is conscientious and generous. When a man raises his hands to him (supplicating), he is shy to turn them away empty and disappointed" (Jāmiʿ At-Tirmidhī 3556).

In human beings, shyness is typically associated with feelings such as embarrassment, awkwardness, insecurity, or apprehension. These emotions often lead a person to avoid certain settings, such as being naked in public. However, in the case of Allāh, there is ijmāʿ (consensus) among the ʿulamāʾ and all Muslims that Allāh does not experience these types of emotions. What is affirmed for Allāh is his avoidance of a particular action, such as refraining from rejecting a sincere duʿā (supplication). The avoidance behavior of Allāh is labelled as shyness. Thus, while human shyness stems from a type of emotional vulnerability and results in avoidance, in the case of Allāh, only the action of avoidance is affirmed and not the emotional state behind it (Tafsīr Al-Khāzin).

Can Allāh be harmed?

Islām teaches that Allāh does not possess weaknesses, yet a Ḥadīth states that humans often 'harm' Allāh by insulting time, but an insult to time actually 'harms' Allāh because he is time (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 4826) [5]. The Arabic word used in the Ḥadīth that is translated as signifying harm is the verb yuʾdhī. However, this word has a broad range of meanings, such as to abuse, to annoy, or to do something displeasing or offensive to someone. For example, the same verb appears in Qurʾān 33:57, which warns that those who annoy (yuʾdhūna) Allāh and his messenger will be cursed by Allāh in the dunyā (worldly life) and in the ākhirah (hereafter). The word has been translated as 'annoy' because Qurʾān 3:176 explicitly states that Allāh cannot be harmed in any way. Thus, to translate this word as signifying harm when used in reference to Allāh is misleading and would not be accurate.

Furthermore, the verb does not always indicate actual harm even when used in reference to human beings. For instance, a Ḥadīth advises that those who have eaten garlic should not immediately go to the masjid (mosque), as the odor may 'harm' others (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 563). Of course, the odor of garlic does not actually harm anyone physically. Here, the meaning is clearly related to annoying or offending others with the odor of garlic.

Does Allāh become tired or bored?

While tafwīḍh is often the preferred approach for dealing with ambiguous references due to its caution in avoiding interpretation, there are some references that are almost universally understood metaphorically. One such example is a Ḥadīth in which the Prophet ﷺ encourages Muslims to perform good deeds in moderation and not to overburden themselves because Allāh does not become ‘bored’ or ‘tired’ until his servant becomes ‘bored’ or ‘tired’ (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 1970). This statement cannot be understood literally, as the Qurʾān clearly affirms that Allāh is never touched by sleep or fatigue (Qurʾān 2:255). Therefore, ʿulamāʾ interpret this Ḥadīth metaphorically to mean that Allāh continues to reward his servants as long as they continue to engage in good deeds; when they stop, the flow of reward ceases accordingly. The main message conveyed here is that moderation in ʿibādah (worship) is generally better than irregular bursts of intense devotion because one is more likely able to be consistent with moderate ʿibādah, while intense devotion will quickly exhaust an individual. The most beloved deeds to Allāh are those done consistently, even if they are small (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 6465).

Does Allāh become sick, hungry, or thirsty?

Another example of a reference that is always interpreted metaphorically is a Ḥadīth that mentions that Allāh will say to a person on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (the Day of Judgment), “O son of Ādam, I was sick, and you did not visit me. I asked you for food, and you did not feed me. I asked you for drink, and you did not quench me” (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2569). The person responds in confusion, asking how he could have visited, fed, or given drink to Allāh, while Allāh is not in need of anything. Allāh then explains that there were people in need who were sick, hungry, or thirsty. Allāh says that had the person tended to these servants, he would have ‘found’ Allāh. The meaning of the Ḥadīth is clearly metaphorical; the message is that to disregard those in need is to disregard Allāh. The Ḥadīth does not imply that Allāh experiences illness, hunger, or thirst. The Qurʾān explicitly states that Allāh is free from need (Qurʾān 35:15).

Do the righteous become Allāh?

A third example of a reference that is universally interpreted metaphorically is a Ḥadīth describing a pious servant of Allāh. The Ḥadīth states that when a person draws near to Allāh through acts of devotion, Allāh says, “I become his hearing through which he hears, his sight through which he sees, his hand with which he strikes, and his foot with which he walks” (Ṣaḥīḥ Al-Bukhārī 6502). This passage cannot be understood literally because it would contradict Qurʾān 42:11, which says that nothing is like Allāh. This Ḥadīth is interpreted metaphorically to mean that a pious servant becomes so devoted to Allāh that all of his actions, including how he utilizes his limbs and senses, are aligned with what is lawful according to the Sharīʿah (Islāmic law) that Allāh has legislated for his creation.

[1] Those who use ta'wīl do not claim absolute certainty about their interpretations. Instead, they present these interpretations as plausible or likely and not definitive. For example, those who interpret the yadayn (hands) of Allāh to mean strength do not insist that this is the only possible meaning. Ultimately, only Allāh can know the complete reality of the ambiguous references mentioned in the Qur'ān or in the Ḥadīth corpus.

[2] See Al-Fawā'id al-Majmūʿah fī al-Aḥādīth al-Mawḍūʿah by Ash-Shawkānī, Al-ʿIlal al-Mutanāhiya fī al-Aḥādīthi al-Wāhiyah and Dafʿ Shubah at-Tashbīh bi-Akuff at-Tanzīh by Ibn Al-Jawzī, Siyar Aʿlām an-Nubalā by Adh-Dhahabī, Silsilah al-Aḥādīth aḍ-Ḍaʿīfah by Al-Albānī, and others.

[3] The ʿulamāʾ differed concerning if Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ saw Allāh during al-Isrāʾ wa al-Miʿrāj. In fact, even the Ṣaḥābah differed over this topic as well. Some say he did not see him, and this was the position of ʿĀ'ishah رضي الله عنها. Ibn ʿAbbās رضي الله عنه held the view that he saw him in a spiritual manner with his heart. The strongest view is perhaps that he saw Allāh with his heart, but ʿĀ'ishah رضي الله عنها only meant to deny that he saw Allāh with his eyes. This reconciles the views of ʿĀ'ishah رضي الله عنها and Ibn ʿAbbās رضي الله عنه. However, some ʿulamāʾ believed that he was given the beatific vision and that he is the only human being that was granted the blessing of seeing Allāh with his eyes before his demise.

[4] The statement that Allāh will be seen just as the moon is seen does not imply that Allāh resembles the moon. Instead, the correct meaning is that just as a large crowd does not obstruct anyone's view of the moon, likewise, on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Day of Judgment), the presence of a vast multitude of people will not prevent any believer from seeing Allāh.

[5] What is meant by the statement that Allāh is time is not that he is literally time, as he is the creator of time, but these words are clarified by the next statement in the Ḥadīth which says that Allāh controls all things and causes the alternation of the night and the day. Thus, he calls himself time because he is in complete control of time. This is like when a king says, "I am the kingdom," signifying his control over such a kingdom; this does not mean the king is literally the kingdom itself.

Leave a comment