Does Islām teach that Allāh is forgetful?

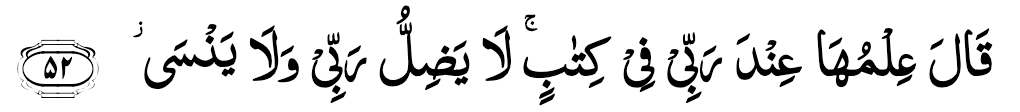

It has been proven that Allāh (God) is omniscient. However, certain āyāt (verses) of the Qurʾān, such as 7:51, 9:67, 32:14, and 45:34, appear to suggest that Allāh forgets, raising the following question: how can these āyāt be reconciled with the concept of Allāh’s omniscience? To answer the objection, it should first be noted that the Qurʾān explicitly denies that Allāh forgets anything.

If the Qurʾān denies forgetfulness for Allāh, then why would some āyāt appear to suggest that Allāh forgets? The answer is that these āyāt utilize the Arabic verb nasiya, which can have a range of meanings, including 'to neglect' or 'to disregard' [1]. For instance, in Qurʾān 7:51, Allāh declares that He will 'forget' the kuffār (disbelievers) on Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Day of Judgment), just as they had forgotten their meeting with him. This should not be taken to mean that Allāh forgets literally. Rather, the correct interpretation is that Allāh will intentionally disregard the kuffār and will remove them from his mercy.

Does Islām advocate for open theism or teach that Allāh lacks knowledge?

Another point of discussion is that some āyāt appear to indicate that Allāh does not have knowledge of future, such as Qurʾān 3:140, 3:166, 5:94, and others. Thus, it is alleged that the Qurʾān teaches open theism [2]. Consider, for example, Qurʾān 3:140, which states that Allāh alternates the days for people. What this means is that he changes the conditions of people, sometimes granting ease to kuffār and hardship to believers, and at other times he grants ease to believers and hardship to kuffār. The underlying wisdom is to test human sincerity; if believers always prevailed, many might practice Islām for worldly gain rather than true faith; if believers were always losing, then the religion could be extinguished. The āyah (verse) states that Allāh alternates the conditions of people in order to know who truly believes. The phrasing may appear to suggest that his knowledge of who believes is dependent on the outcome of the test.

The response is that the Qurʾān explicitly mentions that Allāh knows everything that will occur, including what will happen in the future (Qurʾān 2:255). Furthermore, the Qurʾān teaches that everything occurs due to the will of Allāh, including human actions, but if this is the case, then Allāh certainly knows the future since he determined it (Qurʾān 81:27-9). Thus, it becomes very clear the Qurʾān does not teach open theism. If one claims to believe in the Qurʾān but also professes that the Qurʾān teaches open theism, then this would be a clear contradiction, as the Qurʾān affirms divine foreknowledge. However, one may still wonder why would Allāh use such language that may appear to suggest that he does not know the future. The answer is that since the Qurʾān affirms divine foreknowledge, then such language must be interpreted in a symbolic manner. This is mentioned by the mufassirūn (exegetes) of the Qurʾān, such Ar-Rāzī and others.

Razi then presents several possible interpretations of this phrase. 'First that sincerity may be distinguished from hypocrisy and the person of faith from the rejecter of faith. Secondly, that the friends (awliya') of God may know, though He attributes this knowledge to Himself by way of exalting them. Thirdly, that God may judge in accordance with this distinction, but such judgment cannot happen except with knowledge. Finally, that God may know this (i.e., faith and patience) to have actually occurred from them, although He knew that it would occur. This is because recompense must be accorded for something which actually is, and not for something which is known to occur in the future' (Razi, IX, pp. 14-18) (Ayoub 2:330).

Does Islām teach that Allāh wonders or becomes astonished?

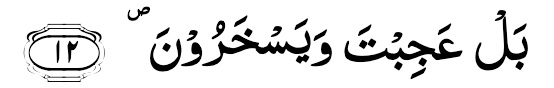

Some critics of Islām allege that the Qurʾān teaches that Allāh wonders or becomes astonished, amazed, or surprised. Qurʾān 37:12 mentions that Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ became astonished (ʿajibta) at the mockery that some members of his tribe exhibited against Islām.

According to the Khalaf qirāʾah, Qurʾān 37:12 says ʿajibtu, which would literally mean, "I became astonished," and 'I' here would refer to Allāh [3]. This has led some critics to claim that Islām attributes a lack of foreknowledge to Allāh because he is supposedly said to become astonished. To address this objection, it must be understood that a single word can have entirely different meanings depending on the context. For instance, in the English language, to say a person is running means that the person is moving, which is very different than saying a computer is running, which means that the computer is functioning. Likewise, when the Qurʾān uses the verb ʿajibta in reference to the Prophet ﷺ, it implies literal astonishment. When the verb ʿajibtu is used in reference to Allāh, it does not denote literal astonishment (Lane 1957). Al-Baghawī mentions in his tafsīr (exegesis) concerning Qurʾān 37:12 that when this verb is attributed to Allāh, it is not to be understood in the human sense of surprise but instead indicates either disapproval when directed toward something despicable or satisfaction when directed to something praiseworthy. For example, a Ḥadīth reports that Allāh is amazed (ʿajiba) with a youth that does not incline towards his desires (Silsilah al-Aḥādīth aṣ-Ṣaḥīḥah 2843). Here, the 'amazement' of Allāh refers not to surprise but to divine pleasure and approval.

Another possible interpretation is the following: Ibn ʿAṭiyyah notes in his tafsīr that when the āyah (verse) uses the word ʿajibtu (I was amazed), even though it appears in the first person, it may still be understood as referring to the first-person perspective of the Prophet ﷺ rather than Allāh. This is not a linguistically implausible reading of the text. In any case, what is unequivocal in Islāmic theology is that Allāh does not wonder or experience literal astonishment, amazement, or surprise in any way that implies a deficiency in knowledge. The Qurʾān affirms that nothing escapes his knowledge (Qurʾān 6:59). Therefore, to claim that Islām teaches that Allāh is ignorant is a misrepresentation of the text and the Islāmic understanding of Allāh.

If Allāh is omniscient, then why are there deformities in the world?

Throughout the Qurʾān, Allāh describes his creation as being perfectly designed, such as Qurʾān 32:7, 67:3, 82:7, 95:4, and so on. At first glance, this claim may appear to conflict with the existence of what seem to be deficiencies in the world, such as death, illness, deformities, and suffering. However, Islām teaches that these aspects do not contradict divine omniscience. Rather, they are due to Allāh’s deliberate design of this worldly life (dunyā). The Qurʾān teaches that life was created as a test for humans and Jinn, where both comfort and hardship serve a purpose: to reveal their moral and spiritual qualities (Qurʾān 67:2). What may appear imperfect from human perspective often contains hidden wisdom. Thus, one should not assume that Allāh is not omniscient because of the deficiencies that are present in the world; these deficiencies were created intentionally. Perfection in the design of creation does not mean the absence of difficulty or the presence of some defect but rather the fulfillment of Allāh’s intended plan, which is to test his creation.

[1] See: https://www.almaany.com/ar/dict/ar-en/%D9%86%D8%B3%D9%8A/#google_vignette.

[2] Open theism is a theological view that affirms God is omniscient, but what open theists mean by 'omniscient' is that God has knowledge of everything that can be known, but there is some information that cannot be known until certain conditions are fulfilled. Open theists do not accept the mainstream understanding of omniscience. In open theism, God has knowledge of all future possibilities but does not know every specific outcome that will occur, such as what people will choose to do with their free will. The motivation of open theism is to preserve human freedom by denying God's exhaustive foreknowledge. The reconciling predestination and free will article elucidates how divine foreknowledge does not contradict free will.

[3] A qirāʾah (pl. qirāʾāt) is a Qurʾānic style of recitation. There is only one Qurʾān, but it can be recited in multiple qirāʾāt. There are ten recognized qirāʾāt that are mutawātir (mass-transmitted), although some ʿulamāʾ (Islāmic scholars) say that seven are classified as mutawātir, while three are considered to be mashhūr, meaning they are well-known and famous, but they do not reach the level of mass-transmission. The qirāʾāt mainly differ in terms of pronunciation, but in some cases, they differ even in terms of wording and meaning, although these different meanings are complementary and harmonious and not contradictory. For instance, Qurʾān 1:4 can be recited as māliki yawmid dīn or maliki yawmid dīn; the former style praises Allāh as an owner, while the latter style praises Allāh as a king. While these meanings are different, they are not mutually exclusive because Allāh is both Al-Mālik (the Owner) and Al-Malik (the King) of everything.

Leave a comment