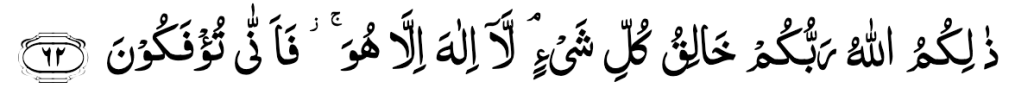

Creator

The necessary being is responsible for the creation of contingent beings, and so the necessary being is Al-Khāliq (the Creator).

Will and life

The necessary being has irādah (will). This particular ṣifah (attribute) highlights that the necessary being is not merely some higher power or some mystical force or energy that unconsciously and mindlessly creates other beings. If the necessary being has will, then this necessitates that the necessary being possesses life and knowledge. The proof that the necessary being possesses will is that it had the choice to either create or not create the world.

- If the necessary being was unable to leave the world nonexistent, then the world would have existed necessarily.

- The world does not exist necessarily.

- Therefore, the necessary being was able to leave the world nonexistent.

This syllogism is valid. As for the first premise, the necessary being created the world, so it obviously has the power to create the world. However, if the necessary was unable to leave the world nonexistent, then the world would have always existed necessarily just as the necessary being. The second premise states that the world does not exist necessarily. Previous articles have already demonstrated that the world is contingent and that there cannot be more than one necessary being in existence. Therefore, the world is not necessary in existence. This demonstrates that the necessary being was able to leave the world nonexistent. Simply put, the necessary being created the world, but it also had the ability not to do so, and so the necessary being has the ability to select between mutually exclusive options. This ability to select between different possibilities is what is labeled as will [1]. Since the necessary being has will, then this shows that it has consciousness and life, and so the necessary being is Al-Ḥayy (The Ever-Living).

An objection to this argument is that artificial intelligence (AI) selects between different options, yet it lacks consciousness and life. The response is that some AI models will always give the same output when a particular input is inputted. There are other AI models that can give different outputs even with the same input across different instances, but in a specific instance of giving an output for a particular input, the AI could not have given a different output, and so it does not possess volition. To put it briefly, AI is reactionary. The necessary being on the other hand had a genuine choice to either create or not to create the world.

Omniscience and the third proof of monotheism

The necessary being willingly chose to create the world, and so it must have some knowledge of how to create the world. However, the necessary being does not possess merely limited knowledge but is omniscient. The proof is as follows:

- Contingent beings possess limited attributes.

- There would be no relevant different to establish necessity if the necessary being also had limited attributes.

- Therefore, the necessary being does not possess limited attributes.

This syllogism is valid. The first premise would likely not be disputed by anyone. However, one might contend that assuming all contingent beings have limited attributes is speculative, but it has been previously established that only the necessary being can possess omnipotence; consequently, all other beings must then have limited power, and so all contingent beings possess a limitation. The second premise asserts that the necessary being cannot have any limitations in its attributes because then there would be no relevant difference between it and contingent beings. For instance, if the necessary being were to possess knowledge limited to exactly 10,000 pieces of information, one could reasonably question why is its knowledge limited to 10,000 pieces of information rather than 9,999 or 10,001 pieces of information. Such a limit would appear arbitrary. Since it is conceivable that this attribute could be either greater or lesser, this implies contingency, and this warrants an explanation.

However, one could reply that perhaps the limit is a necessary one, therefore, no contingency is implied, and there is no warrant for further explanation. Perhaps the necessary being must be necessarily limited. This response is problematic because a contingent being could possess the same limitation, so if the necessary being had knowledge of 10,000 pieces of information, and a contingent being had identical knowledge, then there is no relevant difference to establish necessity. It follows then that the possession of limited knowledge, such as 10,000 pieces of information, is not an attribute that is necessary in itself, since it can equally be possessed by contingent beings. This proves that the attributes of the necessary being do not differ from the attributes of contingent beings in terms of degree but in terms of type. Therefore, the attributes of contingent beings must be limited, while the attributes of the necessary being cannot be limited. Thus, the necessary being must be omniscient. This also establishes that the necessary being cannot share the same exact attributes with contingent beings, and this is another proof of monotheism [2].

Qualitative attributes

It is important not to conflate infinite knowledge and omniscience. Imagine a person knew all positive integers, such as 0, 1, 2, 3, and so on ad infinitum but lacked knowledge of real numbers, such as 1.3, 2.7, 3.3, and so forth. This person would have infinite knowledge but is nowhere near omniscient. Furthermore, some infinities are greater than others. For example, the set of all real numbers is an infinite set that is greater than the infinite set of all integers. The reason for this distinction between infinite knowledge and omniscience is that some may attempt to prove the necessary being’s omniscience through its omnipotence. If the necessary being has the ability to create all possibilities, and there are an infinite number of possibilities, then the necessary being would have infinite knowledge. This is correct, but this does not prove omniscience; this only proves infinite knowledge.

The way to prove omniscience is to show why it would be absurd for the necessary being to have limitations to its attributes, as this would entail contingency. In fact, the necessary being’s attributes are not quantitative but are qualitative because any quantity, including an infinite quantity, can be lesser than other quantities. Thus, even infinite knowledge could entail some form of limitation and contingency. Therefore, it is more appropriate to say that the necessary being has unlimited knowledge without limitation instead of saying that the necessary being possesses an infinite amount of knowledge.

All-hearing, all-seeing, and speech

The necessary being has no limitations to its power and knowledge. Likewise, any abilities that can be derived from these attributes are also limitless. Thus, the necessary being would have the ability to hear, see, speak, and communicate. Due to its limitlessness, the necessary being is As-Samīʿ (The All-Hearing) and Al-Baṣīr (The All-Seeing).

How can the necessary being be limitless and not possess all attributes?

The fact that the necessary being does not have limitations to its attributes does not mean that it possesses all attributes that one can think of. For example, it is incorrect to believe that the necessary being has an infinitely large body because bodies are contingent that depend on space. Contingency contradicts necessity. So, when it is said that the necessary being does not possess limitations, then what this means is that the necessary being possesses all attributes that do not entail contingency or a contradiction.

[1] The necessary being's will is necessary in existence, as are all of its attributes. However, what the necessary being wills is contingent.

[2] If someone argues that it is possible for the necessary being and a living contingent being to share attributes because both are living, then this objection is not valid. The life that the necessary being possesses is fundamentally different from the life of living contingent beings. This distinction applies to all other attributes of the necessary being, such as will, power, knowledge, and so forth. In each case, the necessary being’s qualities are unique in kind and not merely in degree.

Leave a comment