Another objection to the contingency argument: Perhaps there is a beginningless contingent being

In the previous article concerning the contingency argument, the second premise states that every contingent being has a cause beyond itself for its existence. The proof is that any contingent being that comes into existence requires a cause because nothing cannot create or cause anything, nor could the contingent being have created itself. Therefore, any contingent being that comes into existence must have a cause beyond itself for its existence. A possible objection to this proof is that it only establishes that an emergent contingent being must have a cause beyond itself for its existence. One may inquire whether a contingent being never came into being but instead existed eternally without a beginning. The point of this article is to prove that contingent beings cannot be beginningless.

Furthermore, the previous article establishes the existence of a necessary being. It is natural to then ponder how many necessary beings exist. The second purpose of this article is to prove that it is impossible for more than one necessary being to exist. If so, then this would make the case for monotheism.

Contingent beings cannot be beginningless

If a contingent being always existed without a beginning, then this means that its potential to exist was always actualized without a beginning. However, because this being is contingent, it was also possible for this potential to not have been actualized. Since there are two possibilities, then there must be a rationale as to why one possibility was realized instead of the other. One could say that perhaps the non-actualization of the potential was impossible, but this contradicts the very definition of what it means to be contingent; a contingent being does not have to exist, and so there is always a possibility for either actualization or non-actualization. One may then ask what actualized this contingent being’s potential to exist. This contingent being could not have actualized its own potential to exist, as this would be no different than saying that something caused itself to come into existence, nor could nothing have actualized the contingent being’s potential to exist, as nothing does not have the ability to cause or create anything. Therefore, something beyond the contingent being’s existence must have eternally actualized the potential for the contingent being to exist. This makes it clear that no contingent being can exist without a cause beyond itself, even if it were beginningless. A beginningless contingent being’s existence would not be explained by its beginningless.

However, upon closer analysis, contingent beings cannot be beginningless. Take for example that a necessary being eternally actualized the potential for a contingent being to exist, which would make the contingent being beginningless. There are two options:

- This necessary being was able to leave the contingent being non-existent.

- This necessary being was unable to leave the contingent being non-existent.

If this necessary being was able to leave the contingent being non-existent, then the contingent being could not have been beginningless because a beginningless effect cannot be prevented. If the effect is beginningless, then this necessary being would have been unable to leave this contingent being non-existent, which is why the contingent being is beginningless. However, if the necessary being was unable to leave this contingent being non-existent, then this would mean that this contingent being must exist as long as the necessary being exists due to the beginningless effect that originates from the necessary being. This is a contradiction because a necessary being cannot fail to exist, and so it would also be impossible for this contingent being to fail to exist, but this would render this contingent being necessary. A contingent being is always able to fail to exist, and since its inclusion within reality is not a necessity, then its existence is always preventable. If its existence is always preventable, then a beginningless effect from a necessary being cannot generate a beginningless contingent being because a beginningless effect is not preventable. This proves that it is impossible for a necessary being to eternally actualize a contingent being, and so only a necessary being could be beginningless.

Emanationism

It has been demonstrated that contingent beings cannot be beginningless. If a necessary being were to eternally actualize another being, this being would be necessary and not contingent. One may ask: how can a necessary being eternally actualize another necessary being? This leads to the discussion of emanationism. According to emanationism, existence eternally flows from a necessary being. An example of this is the sun and its rays; imagine the sun was beginningless, and if so, then its rays would also be beginningless, and so the sun is the cause for the rays, while the rays are emanations that depend on the sun. Similarly, some may say that a necessary being can cause the existence of another necessary being, and the latter would be an emanation of the former. The necessary being that the emanation depends on has aseity, meaning independent existence, while the emanated necessary being lacks aseity and is eternally dependent upon the independent necessary being for its existence, yet both are co-eternal and exist necessarily without beginning. The necessary being that lacks aseity is necessary ab alio [1]. However, it can be demonstrated that emanationism is false because there cannot be more than one necessary being.

Burhān at-tamayyuz (proof of distinction): only one necessary being can exist

It is impossible for more than one necessary being to exist. The proof is as follows:

- If more than one necessary being existed, then each must be distinguished by some unique specification that others lack.

- It is impossible for each necessary being to be distinguished by some unique specification that others lack.

- Therefore, more than one necessary being does not exist.

This syllogism is valid. As for the first premise, what it means is that if there were two or more necessary beings, then they would have to possess different ṣifāt (attributes) in order to be different. This is because if two beings had no differences whatsoever, then there would only be one being. Imagine if there were two countries that have the same borders, same territory, same people, same weather, same streets, same buildings, and so on. A person then asks what makes these countries different, and he is told that there is not even a single difference between them. The truth is then there would only be one country. There has to be at least one difference between two different things in order to differentiate them. Therefore, the first premise is true. [2]

As for the second premise, what it means is that necessary beings cannot be distinguished with different ṣifāt. To understand, imagine one necessary being has a particular attribute labeled as S. Another necessary being does not possess the attribute of S, and this is what distinguishes these two necessary beings. Now it should be asked why does one necessary being possess S when it is possible for necessary beings to exist without S. The problem with even allowing the possibility of different necessary beings would make each a possible and contingent being because each one did not have to be what it is; the very existence of multiple necessary beings would be proof that they are contingent, but this would be self-refuting and contradictory. Therefore, necessary beings cannot be distinguished with any differences whatsoever, but if they cannot be distinguished, then they would all be the same for nothing would differentiate them. If they are all the same, then there is only one necessary being.

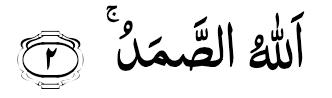

Burhān at-tamayyuz is proof for monotheism and proof that there cannot be more than one necessary being; it also disproves emanationism. Since only one necessary being exists, then only one beginningless and uncreated being exists. The necessary being is Al-Wāḥid, meaning the One, Al-Aḥad, meaning the Absolutely One and Unique, Al-Qayyūm, meaning it is uncreated and self-subsisting, and Aṣ-Ṣamad, meaning everything relies on it for everything, but it relies on no one for anything. All else in existence is contingent and had a beginning. The necessary being is Al-Awwal, meaning the First, because it existed when all else did not exist, and it is Al-Ākhir, meaning the Last, because it will exist forever even if others cease to exist (Qurʾān 57:3).

[1] It may be said that the dependent necessary being is contingent in the sense that it is dependent upon another for its existence, but it is not contingent in the sense that it cannot fail to exist. If a dependent necessary being can exist, then what is dependent is not necessarily able to fail to exist, and this would only apply to a dependent necessary being, while that which can fail to exist is always dependent, and this would apply to contingent beings. It is important not to fall into an equivocation fallacy when using the word 'contingent' so that one may properly understand the argument. Ultimately, however, it can be demonstrated that there cannot be more than one necessary being, so everything else in existence besides the necessary being is contingent, and all contingent beings can fail to exist and are dependent. If so, then everything that is dependent can fail to exist, and everything that can fail to exist is dependent.

[2] Even identical twins are not absolutely identical because they occupy different positions in space.

Leave a comment