A contingency argument is a type of cosmological argument that usually seeks to argue for the existence of a necessary being based on contingencies that exist in reality. This article will demonstrate that a necessary being exists and that the universe is a contingent being. The contingency argument can be formulated in a variety of ways and has plenty of advantages compared to other cosmological arguments, such as the kalām cosmological argument, which may rely on particular notions of time. The argument is as follows:

- A contingent being exists.

- Every contingent being has a cause beyond itself for its existence.

- The set of all contingent beings cannot be caused by a contingent being.

- Therefore, a necessary being exists.

This syllogism is valid, and now the premises will be evaluated.

Premise 1

The first premise states that a contingent being exists. This is a fact that practically everyone accepts. A contingent being is a possible being that does not have to exist, and so any being that comes into existence or becomes nonexistent is contingent and possible. A contingent being that could end, even if it never does, is still contingent and possible. A contingent being that could come into existence, but has not yet come into existence, is still contingent and possible, but it is not actual. On the other hand, a contingent being is always actual and exists necessarily and not contingently, meaning it must exist, and so a necessary being always existed without beginning and will always exist without end; its nonexistence is impossible. This is the definition of a necessary being, and the point of the argument is to prove that such a being exists.

Objection 1.1: Does anything exist?

One may question if anything exists. Perhaps everything that exists is an illusion. Nevertheless, if one doubts that anything exists, then one’s doubts exist. Even if everything that exists is an illusion, then an illusion exists, and this is sufficient enough for the argument.

Objection 1.2: Does anything contingent exist?

One may claim that everything that exists is necessary. For example, one might argue that when a baby is born, the baby was not truly nonexistent prior to its birth or its conception in the womb but was instead particles that were later rearranged into the configuration of a baby. Thus, one could argue that the baby has always existed in some form, and the changes that lead to its birth merely represent a transition between configurations, suggesting that the matter that the baby is composed of is necessary. Perhaps everything then, or at least the matter they are composed of, is necessary. The response to this is that the particular rearrangements of matter are contingent, and this is sufficient enough for the argument.

Objection 1.3: Determinism is true, therefore, everything is necessary

Another common objection is that determinism refutes the idea of anything being contingent. Determinism means that all events that occur are causally inevitable. Imagine that a house was built on a certain day. If determinism is true, then it was inevitable that this house would be constructed on this particular day. However, just because the existence of the house is inevitable does not mean that the existence of the house is necessary. This would be a fallacy of equivocation, as a person who makes this objection is equivocating on the meaning of ‘necessary’ and is conflating its meaning with ‘inevitability’. If the house was necessary in existence, then it could not have had a beginning, nor could it ever end. The truth or falsity of determinism does not negate the existence of contingent beings.

Premise 2

The second premise states that every contingent being has a cause beyond itself for its existence. When a contingent being comes into existence, one may ask why did this contingent being come into existence. There are three options:

- The contingent being came into existence without a cause.

- The contingent being caused itself to come into existence.

- The contingent being was caused by something other than itself to come into existence.

Objection 2.1: Perhaps something can come into existence without a cause

The first option is impossible. Everything that has been observed to come into existence appears to have a cause, but just because everything that has been observed to come into existence has a cause does not mean that everything that begins to exist has a cause. This is an inductive fallacy and a faulty generalization. One cannot be sure that such inductive reasoning is correct in this regard. This is no different than saying that every swan that has been observed is white, so all swans are white. This is a fair objection, but the first premise does not rest solely on intuition or induction. A deductive argument demonstrates the impossibility of any being emerging into existence without a cause.

- Nothing is the absence of everything.

- Nothing is devoid of abilities.

- Therefore, nothing lacks the ability to cause or create anything.

This syllogism is valid. Premise 1 is true by definition, which would mean nothing has no abilities, and so it is impossible for nothing to cause or create anything. Thus, if anything comes into existence without any apparent cause, there must be a cause, even if the cause was not observed. One does not need to observe every instance of something coming into existence in order to prove that anything that begins to exist must have a cause for its existence, just as one does not need to observe every square in reality in order to know that all squares are four-sided. Squares are four-sided by definition, and this is enough to conclude that all squares are four-sided, even if one has not observed all squares; similarly, nothing lacks the ability to cause or create anything. Therefore, anything that begins to exist must have a cause for its existence, even if one did not observe every instance of something coming into existence.

Created from nothing versus by nothing

If something cannot come into existence by nothing, then how can Allāh (God) create ex nihilo (out of nothing)? The answer is that there is a difference between something being created by nothing, as opposed to Allāh creating something from nothing. The former violates causality, while the latter does not. When it is said that Allāh created something out of nothing or from nothing, what this means is that he can create something without preexisting material. It is not that Allāh is transforming nothing into something, as nothing is simply nothing and does not change; instead, he simply brings creation into existence. Some may consider it strange that Allāh is able to create something without preexisting material, but there is nothing logically impossible about this. However, it is logically impossible for something to come into existence by nothing, which means without any cause whatsoever.

Objection 2.2: The quantum realm violates the causal principle

Those who argue that something can occur or begin to exist without a cause often do so by relying on the quantum realm as an example, which demonstrates that virtual particles can apparently come into existence from nothing. However, what these people mean by ‘nothing’ are in fact quantum fluctuations or prior physical conditions, which are not truly nothing. For example, the Islāmic researcher, Hamza Tzortzis, mentions this in his book when analyzing Professor Lawrence Krauss’s book, A Universe from Nothing.

"Krauss's 'nothing' is actually something. In his book he calls nothing 'unstable', and elsewhere he affirms that nothing is something physical, which he calls 'empty but pre-existing space'. This is an interesting linguistic deviation, as the definition of nothing in the English language refers to a universal negation, but it seems that Krauss's 'nothing' is a label for something. Although his research claims that 'nothing' is the absence of time, space and particles, he misleads the untrained reader and fails to confirm (explicitly) that there is still some physical stuff. Even if, as Krauss claims, there is no matter, there must be physical fields. This is because it is impossible to have a region where there are no fields because gravity cannot be blocked. In quantum theory, gravity at this level of reality does not require objects with mass but does require physical stuff. Therefore, Krauss's 'nothing' is actually something. Elsewhere in his book, he writes that everything came into being from quantum fluctuations, which explains a creation from 'nothing', but that implies a pre-existent quantum state in order for that to be a possibility." [1]

Tzortzis also quoted Professor David Albert who reviewed Professor Krauss’s book as well.

"But that’s just not right. Relativistic-quantum-field-theoretical vacuum states — no less than giraffes or refrigerators or solar systems — are particular arrangements of simple physical stuff. The true relativistic-quantum-field-theoretical equivalent to there not being any physical stuff at all isn’t this or that particular arrangement of the fields —it is just the absence of the fields! The fact that some arrangements of fields happen to correspond to the existence of particles and some do not is not any more mysterious than the fact that some of the possible arrangements of my fingers happen to correspond to the existence of a fist and some do not. And the fact that particles can pop in and out of existence, over time, as those fields rearrange themselves, is not any more mysterious than the fact that fists can pop in and out of existence, over time, as my fingers rearrange themselves. And none of these poppings — if you look at them aright — amount to anything even remotely in the neighborhood of a creation from nothing." [2].

Objection 2.3: Perhaps something can cause itself to come into existence

The second option is also impossible because no being can create itself. How can a being create itself when it was nothing and did not exist in order to create itself? If a being already exists, how can it create itself when it already exists? Some may respond that particular organisms, such as bacteria, perform asexual reproduction and produce identical offspring. The problem with this response is that even though bacteria produce identical offspring, the offspring are not the original bacteria; during asexual reproduction, bacteria do not create themselves but produce identical copies. Only the third option remains, therefore, contingent beings that come into existence were caused by something other than themselves to come into existence.

Premise 3

The third premise states that the set of all contingent beings could not have been caused by a contingent being. The reason for this is because it is contradictory for a contingent being to cause the set of all contingent beings as the contingent being would itself be included in the set of all contingent beings. This demonstrates that the cause of the set of all contingent beings is not contingent. Whatever is not contingent is necessary. Therefore, a necessary being exists.

Objection 3.1: There may be an infinite regress of contingent beings causing other contingent beings to exist

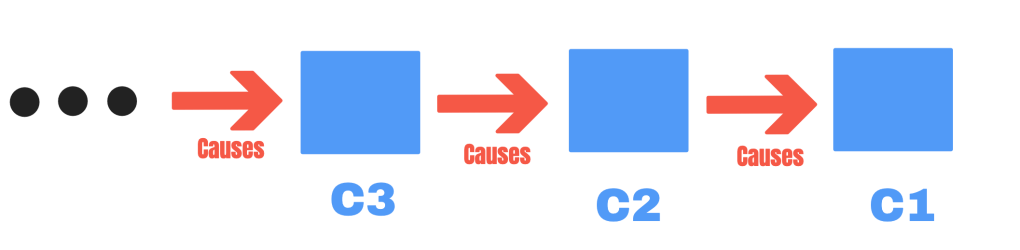

One could claim that a contingent being may have been caused to come into existence by another contingent being that was also caused to come into existence by another contingent being ad infinitum. Since each contingent being is explained by another contingent being, then one could claim that there is no need for a necessary being. An illustration may help to clarify the claim.

The response to this objection is that infinite regress is impossible; this is because if there were an infinite regress of contingent beings causing other contingent beings to exist, then this would mean that each contingent being came into existence after an endless number of tasks have been completed. A helpful analogy is a boss who tells his employee that he will pay him after completing an endless number of jobs. Will the employee ever finish an endless number of jobs and get paid? Certainly not, and likewise, there must have been a first contingent being in order to stop the infinite regress. The cause of this contingent being’s existence could not have been nothing, nor could it have been itself, but the cause must have been something other than itself. This cause cannot be contingent because then it would be the first contingent being, which would only add to the regress. Therefore, the cause of the first contingent being cannot be contingent, which means that the cause of the first contingent being must be a necessary being.

Response to the question: Who created God?

If anything that has a beginning requires a cause, then each cause that has a beginning would also require a cause, resulting in an infinite regress [3]. To avoid this, there must be an uncreated and beginningless being that exists outside the chain of created things. This necessary being serves as the ultimate explanation and foundation for the existence of everything else, providing a coherent stopping point to the regress. To ask who created God or who created the necessary being is akin to asking who created the being that is uncreated and beginningless.

The contingency argument works even if an infinite regress is possible

While mainstream Sunnī Islām denies the possibility of an infinite regress, the contingency argument succeeds even if an infinite regress is possible. The reason for this is because even if there were an infinite regress of contingent beings causing other contingent beings, the whole chain is not explained. One may object and say that if the existence of each contingent being is explained due to another contingent being, then the whole chain is explained, but this is false. Each contingent being could have not existed, and if every member on the chain is contingent, then the entire chain is contingent and did not have to exist, which means there could have been a different chain of contingent beings causing other contingent beings, or there did not have to be any chain whatsoever. One may then ask why does a particular chain of contingent beings exist when its existence is not necessary. The entire chain cannot be due to a contingent being as this falls into the same problem, therefore, there must be a necessary being that grounds the existence of contingent beings and constitutes the foundation of reality [4].

Summary

Contingent beings that come into existence need something beyond themselves to actualize their potential to exist. The set of all contingent beings cannot be caused by a contingent being, as this contingent being would be included in the set of all contingent beings. Therefore, a necessary being is the ultimate cause and foundation for the existence of all contingent beings. Even if there were an infinite regress of contingent beings causing other contingent beings, the whole chain of contingent beings is itself contingent and could have been different, and this warrants an explanation that does not rely on a contingent being. All of this leads to the conclusion that a necessary being exists and is the reason for the existence of everything else.

[1] Tzortzis, Hamza A. The Divine Reality: God, Islam and the Mirage of Atheism. 2019, p. 56.

[2] Albert, David. “On the Origin of Everything.” The New York Times, March 23, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/books/review/a-universe-from-nothing-by-lawrence-m-krauss.html?_r=0.

[3] Note that it is correct to say that anything that has a beginning must have had a cause for its existence, while it is incorrect to say that anything that exists has a cause for its existence.

[4] Contrary to mainstream Sunnī Islām, Ibn Taymīyyah, a Sunnī Islāmic scholar, believed that Allāh has always been creating, so one creation was always preceded by another creation ad infinitum. A common misconception is that Ibn Taymīyyah believed that the world is co-eternal with Allāh; this is false. What Ibn Taymīyyah believed is that creation as a whole did not have an absolute starting point, and so while one creation was always preceded by another creation ad infinitum, no particular creation existed co-eternally with Allāh.

Leave a comment